(Still) Forgetting the Freedom of Assembly

A recent federal appellate decision shows the continued neglect of the right of peaceable assembly

One of my principal scholarly interests is the First Amendment’s right of assembly. As I noted in an earlier post:

The right of assembly allows people to form and gather in groups of their choosing and to express their values and beliefs even when—and perhaps especially when—those views challenge or upset government officials. It is one of our foundational civil liberties. And most Americans can’t even name it.

A recent decision by the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit illustrates the ongoing neglect of assembly.

In the News

Last month, a Sixth Circuit panel affirmed the dismissal of a lawsuit challenging restrictions issued by Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. A group of churches, religious schools, parents, and students had sued Governor Beshear for a ban he had issued on in-person learning at all private and public elementary and secondary schools in Kentucky following the COVID-19 surge in the winter of 2020. The ban has long since been lifted, but the alleged constitutional violations remain.

The panel’s opinion addresses a number of different legal issues, but most germane to this post is its treatment of the petitioners’ final claim that the governor’s order “violated their rights to assemble peacefully and associate freely.”

The opinion dismisses this claim for procedural reasons but then proceeds to analyze its merits, and in doing so, introduces a misguided analysis to Sixth Circuit precedent. Among other errors, the opinion fails to provide any analysis of the right of assembly and focuses entirely on the separate and distinct right of association (and its component parts of intimate and expressive association).

In My Head

When I came across the Sixth Circuit’s decision, I was surprised to see a federal appellate court completely ignoring a claim based on one of the five individual rights in the text of the First Amendment. When courts fail to consider the values and protections underlying the right of assembly, they weaken constitutional guarantees for everyone. Our ability to express our own views and dissent from majoritarian norms does not rest on speech alone but also requires the right of the people to form, gather, and exist in groups.

Given the problems with this opinion, I was pleased to learn the petitioners have asked to have the three-judge panel decision reviewed by the entire Sixth Circuit (through what is called en banc review).

I added my own views about the importance of reviewing the panel’s mistaken assembly analysis in an amicus brief filed earlier this week. I was fortunate to work with the students and faculty at Pepperdine’s Religious Liberty Clinic (Matteson Landau, Grace Mulvaney, Daniel Chen, Eric Rassbach, and Michael Helfand), as well as Megan Lacy Owen and Noel Francisco at Jones Day.

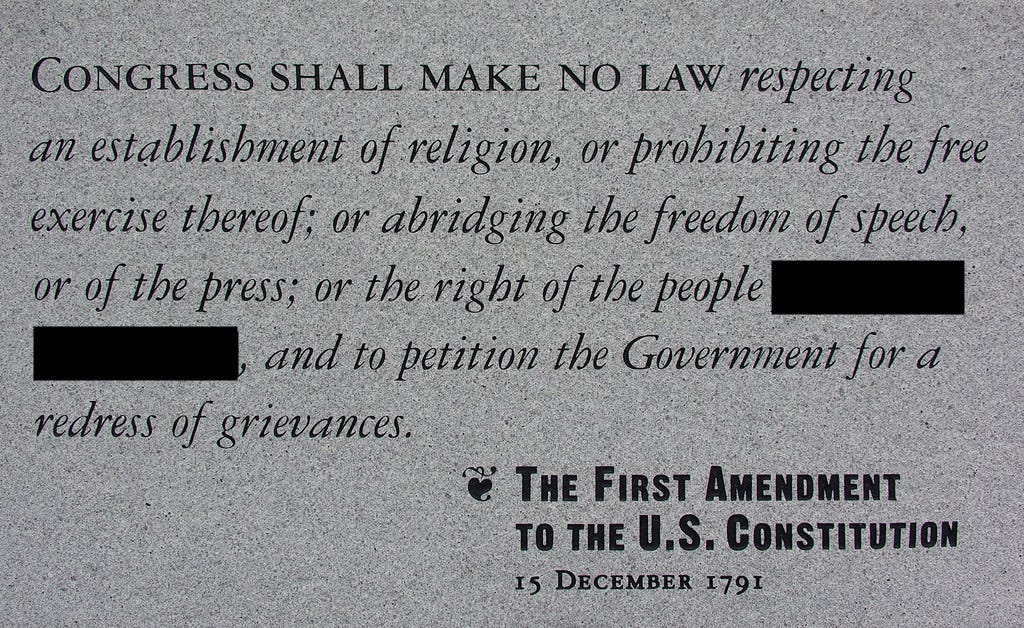

Our amicus brief emphasizes that “assembly is an independent and freestanding right” and “the panel’s opinion ignores the clear text and history of this right by focusing instead on the separate rights of intimate and expressive association.” The brief notes that the right of assembly is textually set apart from other First Amendment freedoms, including those of speech, petition, and religious exercise. And assembly precedes the non-textual right of association, which was first recognized by the Supreme Court in 1958.

The brief also traces some of the history of the right of assembly. Debates in the First Congress over the Bill of Rights suggest that assembly is an important and freestanding right. Theodore Sedgwick, for example, tried to strike assembly from the First Amendment’s text, arguing: “If people freely converse together, they must assemble for that purpose; . . . it is certainly a thing that never would be called in question.” John Page responded by noting that “the power of assembling” extended to purposes beyond those “expressly specified in the First Amendment.” Sedgwick’s motion to strike failed by “a considerable majority.”

This debate in the First Congress also shows that freedom of religious assembly—as distinct from expressive or petitionary assembly—is at the core of the assembly right. In response to Sedgwick, Page invoked William Penn’s famous prosecution for gathering to worship as a Quaker in violation of the 1664 Conventicle Act, which prohibited assembly for religious meetings not sanctioned by the Church of England. Penn’s alleged offense had nothing to do with petition—his attempted assembly was an act of religious worship.

While the Supreme Court has not addressed the right of assembly in many decades, earlier decisions have clearly recognized its importance. We highlight a number of these in our brief, including:

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U.S. 353 (1937) (incorporating freedom of assembly against the States)

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U.S. 242, 250 (1937) (acknowledging the independence of the assembly right from the freedom of speech by referring to the two separately: “[T]he power of a state to abridge freedom of speech and of assembly is the exception rather than the rule”)

Hague v. Committee for Indus. Org., 307 U.S. 496 (1939) (referring to “freedom of speech and freedom of assembly” as separate “rights”)

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U.S. 516 (1945) (“The right thus to discuss, and inform people concerning, the advantages and disadvantages of unions . . . is protected not only as a part of free speech, but as part of free assembly.”)

West Virginia v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943) (the “freedom of worship and assembly,” in addition to “free speech,” are among the “fundamental rights that may not be submitted to a vote”)

As our brief notes, the Sixth Circuit has also recognized the independent right of assembly, referring just two years ago to the “right to assemble and to free speech” as “bedrock constitutional guarantees.” Ramshek v. Beshear, 989 F.3d 494 (6th Cir. 2021).

I am hopeful that the Sixth Circuit will take this case for en banc review and correct the flawed panel analysis.

In the World

I wrote my first book on the right of assembly: Liberty’s Refuge: The Forgotten Freedom of Assembly. I open the book by calling attention to the historical importance of assembly in this country:

The freedom of assembly has been at the heart of some of the most important social movements in American history: antebellum abolitionism, women’s suffrage in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the labor movement in the Progressive Era and the New Deal, and the Civil Rights Movement. Claims of assembly stood against the ideological tyranny that exploded during the first Red Scare in the years surrounding the First World War and the Second Red Scare of 1950s’ McCarthyism. . . . In 1939, the popular press heralded assembly as one of the “four freedoms” central to the Bill of Rights. Even as late as 1973, John Rawls characterized it as one of the “basic liberties.”

And I underscore the importance of assembly as distinct from the separate rights of speech and association:

The central argument of this book is that something important is lost when we fail to grasp the connection between a group’s formation, composition, and existence and its expression. Many group expressions are only intelligible against the lived practices that give them meaning.

These are some of the realities that can go unnoticed when courts altogether ignore claims based on the First Amendment’s right of assembly.

Thanks to a Creative Commons license (which I wrote about in this post), the entire book is freely available online for anyone to read—students, professors, policymakers, federal appellate law clerks reviewing en banc petitions—really, anyone.

Way to go, John. Freedom to assemble is indeed separate from the individual freedoms listed.