What is the Right of Assembly?

One of the least known provisions of the First Amendment is also one of the most important

The title of this newsletter is Some Assembly Required. In previous posts, I have covered a number of related themes, including a definition of pluralism, the value of interfaith engagement, and the importance of civic discourse. (You can find a complete list of my previous posts here).

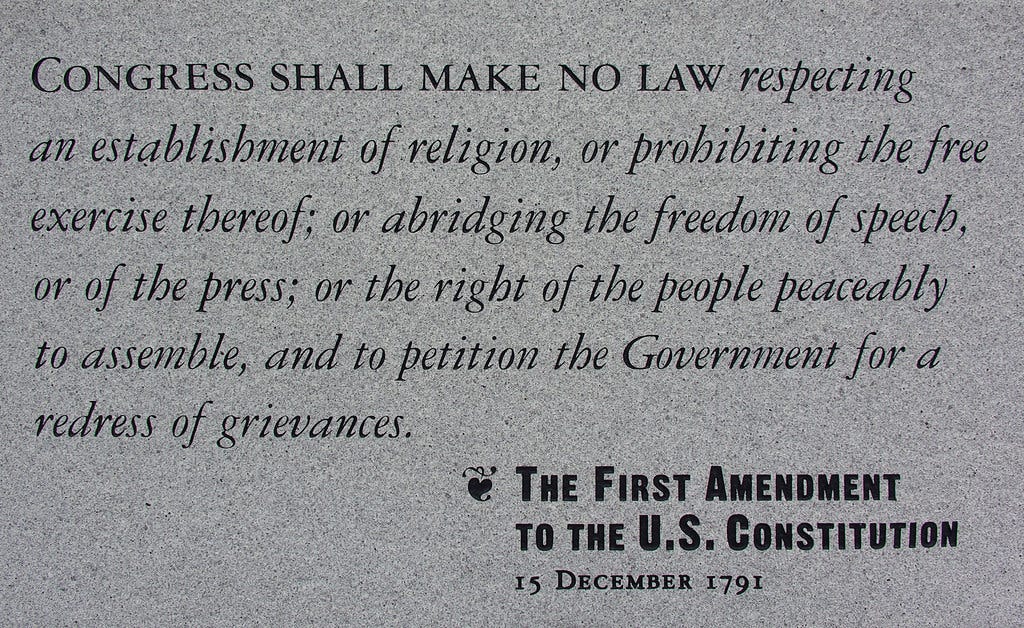

I have not yet introduced the namesake of this newsletter: what the First Amendment refers to as “the right of the people peaceably to assemble.”

The right of assembly allows people to form and gather in groups of their choosing and to express their values and beliefs even when—and perhaps especially when—those views challenge or upset government officials. It is one of our foundational civil liberties. And most Americans can’t even name it.

I am one of a handful of scholars whose core writing focuses on the right of assembly. I remember when I first thought to look into it. I was working on a free speech case while clerking for a judge and happened to pause at the Assembly Clause as I glanced at the text of the First Amendment. It occurred to me that I knew nothing about the right of assembly. And after a few hours of research, it occurred to me that nobody else knew anything about it either. The Supreme Court hadn’t taken an assembly case in forty years, and nobody had written on it in decades. One of the core rights of the First Amendment had been essentially ignored in the modern era.

When I started graduate school after practicing law, I knew I wanted to focus my dissertation on the right of assembly. That eventually became my first book, Liberty’s Refuge: The Forgotten Freedom of Assembly.

In the News

In 2019, the Freedom Forum Institute reported that only 12% of respondents could identify the right of assembly in the First Amendment. This lack of familiarity is particularly unfortunate given how frequently Americans across the political spectrum encounter restrictions on their right to assemble. Tell me the cultural, religious, or political issue you care about the most, and I can find somewhere in this country where the right to assemble on behalf of that issue is under attack.

For example, officials in Ferguson, Missouri, imposed unconstitutional limits on protesters following the death of Michael Brown. In Massachusetts, the American Civil Liberties Union failed to support a protester outside an abortion clinic. In New York City, undercover police officers infiltrated Muslim student groups. Republicans and Democrats both threaten to strip tax-exempt status from organizations they don’t like. And political leaders from both major parties have sought to limit political protests against them.

Restrictions on assembly also emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some of these were justified; others overreached and limited peaceful protests or religious assemblies without a compelling justification for doing so.

In case after case, government officials interfere with the assembly rights of nonviolent groups around this country.

Just this week, Amnesty International announced a new global campaign to confront the “unprecedented and growing threat across all regions of the world” to the right to protest. In addition to flagging violations around the world, Amnesty International’s report cited numerous examples in the United States.

In my Head

One of the oddities of the history of American constitutional law is a fundamental misreading of the Assembly Clause by judges and scholars who for decades mistakenly assumed that the First Amendment only guaranteed the right of assembly for purposes of petitioning the government. The interpretive error originated in an 1886 Supreme Court opinion, Presser v. Illinois. Relying on an earlier case, Justice William Woods wrote that the First Amendment protected the right to assemble only if “the purpose of the assembly was to petition the government for a redress of grievances.”

One of the arguments of my first book was to show how the text, history, and norms of the First Amendment make clear that assembly and petition are two distinct rights. Assembly protects the formation, expression, and boundaries of the groups of civil society. Petition gives individuals or groups reasonable access to government officials to make their views known.

The modern Supreme Court has come close to remedying its earlier error conflating assembly with petition. Last year, the Court decided Americans for Prosperity v. Bonta, an important case involving disclosure of membership lists of private organizations. During the oral argument, three Justices inquired about the right of assembly. Questioning the lawyer for the petitioners, Justice Kavanaugh asked:

Do you agree on the text of the First Amendment that the freedom to peaceably assemble is distinct from the freedom to petition the government for a redress of grievances?

Justice Barrett followed later with a related question about the right of assembly, and Justice Kagan also referenced an amicus brief arguing that the Court consider the assembly implications in this case. Unfortunately, the Court’s opinion in Bonta failed to acknowledge the importance of assembly or correct its earlier error in Presser. Justice Thomas’s concurrence, however, noted that “the text and history of the Assembly Clause suggest that the right to assemble includes the right to associate anonymously.”

In future cases, it will be important for the Court to clarify the importance and scope of the right of assembly. As I wrote in a 2019 Atlantic article:

Negotiating conflicts through politics inevitably produces winners and losers—those elected to office and those defeated, those who benefit from policies and those who suffer under them. But no matter who prevails in the political process, a democratic government must protect the groups and spaces where people can continue to pursue and express their alternative visions of the common good. This commitment is not cost-free. The right to protest risks disruption, instability, and possible political change. The ability to form and maintain groups of people’s choosing means some groups will exclude those who don’t share their beliefs and values. Tolerating assemblies that do not advance majoritarian understandings of the common good means tolerating expression and practices that the majority may not like.

The right of assembly is not unlimited; the textual constraint on “peaceable” assembly offers one important clue to its limits. But proper constraints on assembly still leave room for the political and social disagreement that inevitably characterizes our pluralistic society:

Americans of all political stripes can choose to exercise the right of assembly as a peaceable but firm reminder that e pluribus unum was always more aspirational than embodied, knowing that the many must still work to live together in spite of their differences.

In the World

The past few years have seen an uptick in scholars from law and other disciplines focusing on the right of assembly. The three scholars other than me who have most consistently written about it are Ashutosh Bhagwat (UC Davis Law), Tabatha Abu El-Haj (Drexel Law), and Timothy Zick. I have benefited tremendously from their work, and each of them has also graciously engaged with my ideas in ways that have consistently sharpened my thinking and writing.

I imagine that I’ll return to all of their work in future posts, but today I’d like to highlight Professor Bhagwat’s 2020 book, Our Democratic First Amendment. Bhagwat’s book demonstrates the interconnectedness of the various rights in the First Amendment. This synthetic work is itself rare for First Amendment scholars, most of whom focus either on speech or religion. Bhagwat’s attention to assembly enhances the connections between and among the First Amendment’s other rights.

Our Democratic First Amendment also explores various theoretical justifications underlying the First Amendment, including not only democratic theory but also theories of sovereignty and citizenship. All of these have a great deal of relevance today.

Ahh, the importance of punctuation. The comma between the right to peaceably assemble and [the right] to petition...as contrasted with the semi-colons separating the first two rights...therein lie the seeds of debate.

John, as always, and especially for this legal layperson, a valuable read. I will confess to being one of the multitude who was fundamentally ignorant of the provisions of the first amendment, in particular this right of assembly. I'm glad you made it your passion.