Expressive Association Isn't Enough

Some skepticism over David French’s recent tribute to a (twice) made-up right

Readers familiar with Some Assembly Required will know by now that I regularly draw attention to the right of assembly. Some publicly visible assemblies are spontaneous, but most are not. Most gatherings are preceded by groups of people who have been drawn together by similar interests and goals. Today, these antecedent groups are sometimes protected under the right of association instead of the right of assembly. The difference is more than just words.

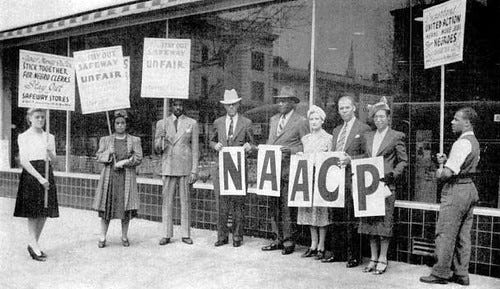

Unlike assembly, association does not appear in the text of the Constitution. Instead, the Supreme Court first recognized this right in its 1958 decision, NAACP v. Alabama. In doing so, the Court invoked unenumerated rights in its language and reasoning—an approach that it adopted a few years later in announcing a right to privacy in Griswold v. Connecticut (the decision that laid the groundwork for Roe v. Wade).

Twenty-six years after NAACP v. Alabama, the Court split the right of association into different subsets in Roberts v. United States Jaycees: intimate association, expressive association, and (by implication) associations that were neither intimate nor expressive. In other words, intimate and expressive association are derivative rights of a right of association that is itself derivative of the right of assembly: they are made-up rights twice over. And they are largely untethered from history, theory, or doctrine.

I wrote last week about intimate association and the confusing and artificial lines that it has created around protections for groups that foster our sense of belonging and identity formation. Today, I turn to expressive association.

In the News

On Sunday, David French drew attention to the right of expressive association, which ostensibly protects our ability to join with others to promote our shared views. Quoting law professor David Bernstein, French described expressive association as “a necessary adjunct to the right of freedom of speech.”

French emphasized that these protections for private groups are essential to our democratic experiment:

This is how pluralistic nations thrive. Citizens are not dependent on government or aristocracy to form and sustain the organizations that give their lives direction and purpose. Political associations help citizens influence the government. Cultural affinity groups sustain the arts and shape values. Religious organizations help preserve the values that provide eternal, transcendent meaning to people’s lives.

French reflected on some recent legal and policy decisions implicating associational rights and concluded that “when it comes to preserving the indispensable right of freedom of expressive association, our American system is delivering” and our liberties are “more secure than they’ve ever been.”

In my Head

French’s embrace of expressive association as a “necessary adjunct” to free speech repeats a common but incorrect understanding that positions our ability to form and join groups as ancillary to a seemingly more important free speech right. That’s the wrong way to think about it. Our ability to speak or express our beliefs and values is predicated on our ability to form and join groups where we develop and cultivate those beliefs and values. French is correct to describe free speech as “fatally degraded” without protections for the groups from which speech emerges, but that hardly makes expressive association an “adjunct” right.

Contrary to French’s contention that all is well with expressive association, the legal doctrine is thin and easily malleable. The problems began with the Supreme Court’s initial recognition of the right of association in 1958. In an odd twist of history, the cases involving the right of association that came before the Supreme Court in the decade or so following NAACP v. Alabama came from two litigants: the NAACP and the Communist Party of the United States of America. In case after case, the Court upheld associational protections for the NAACP and denied them to the Communist Party. Most of us may like those substantive outcomes, but protecting sympathetic groups and leaving unsympathetic ones unprotected is not a good way to create coherent precedent.

In the Jaycees case, expressive association failed to protect an all-male civic association in its desire to remain male-only. Sixteen years later, in Boy Scouts v. Dale, it upheld the right of the Boy Scouts to exclude a gay scoutmaster. And ten years after that, in Christian Legal Society v. Martinez, the right of expressive association provided no protection to a Christian student group that wanted to limit its members to Christians.

Expressive association is even more confusing in the lower courts. In dozens of decisions over the past few decades, courts have concluded that groups ranging from fraternities to motorcycle clubs to nudist colonies are not sufficiently “expressive” to qualify for the protections of expressive association. These cases did not weigh competing government interests against the right of expressive association but instead denied the possibility of the right altogether by determining that the affected groups were not expressive.

As I wrote in my 2016 book, Confident Pluralism: Surviving and Thriving Through Deep Difference:

The category of nonexpressive association obscures the fact that all associative acts have expressive potential: joining, gathering, speaking, and not speaking can all be expressive. It becomes very difficult, if not impossible, to police this line apart from the expressive intent of the members of the group. And many groups that might at first blush seem to be nonexpressive could in fact articulate an expressive intent.

David French is not alone in turning to expressive association as an anchor protection for our civil liberties. But I do not share his optimism that the theory or doctrine of that right is either healthy or stable. One consequence of this instability is that judges are left to decide which of our private groups are sufficiently expressive to warrant possible constitutional protections and which groups will be left unprotected. Based on the judicial record in the years since the Court first announced the right of expressive association, I am less confident than David that this kind of judicial discretion will lead to favorable outcomes.

In the World

In researching my first book, Liberty’s Refuge: The Forgotten Freedom of Assembly, I reviewed the scholarly books and articles written on the rights of assembly and association after the Supreme Court first recognized the latter in NAACP v. Alabama. One of the most helpful was Glenn Abernathy’s 1961 book, The Right of Assembly and Association.

Abernathy suggested that NAACP v. Alabama had placed the right of association within an “expanded meaning” of the right of assembly, and that association was “clearly a right cognate to the right of assembly.” The briefs before the Court in NAACP v. Alabama also made clear that association derives from assembly. Unfortunately, subsequent commentators recast association as a speech-based right, which made protections for groups dependent upon their speech—their expressive association. Writing twenty-three years before the Court formally embraced the speech-based justification for association, Abernathy suggested a different alternative:

It must be noted that [NAACP v. Alabama] does not clearly extend the First Amendment protection to all lawful affiliations or organizations. What Justice Harlan discusses is the association “for the advancement of beliefs and ideas.” Clearly a vast number of existing associations would fall within this description, but it is questionable whether the characterization would fit the purely social club, the garden club, or perhaps even some kinds of trade or professional unions. No such distinction has been drawn in the cases squarely involving freedom of assembly questions. The latter cases emphasize that the right extends to any lawful assembly, without a specific requirement that there be an intention to advance beliefs and ideas.

Abernathy’s analysis was correct in 1961, and it remains correct today.

I hope you'll write more on this theme, John. Specifically, more on what worries you and why, and then expand on how the right of expressive association can be strengthened and (or?) clarified.