The Rights and Responsibilities of Protest Leaders

A recent federal appellate court ruling places too much responsibility on protest leaders

Far too often, policymakers and law enforcement officials across the country overregulate peaceful protests and unconstitutionally constrain protected First Amendment activity. On the other hand, protests are often dynamic and unstable, and once they move from peaceful to violent or otherwise lawbreaking, law enforcement officials may rightly intervene to protect the safety of bystanders, other protesters, and police officers. But what happens when violence does occur? Who is responsible for the resulting harms?

In the News

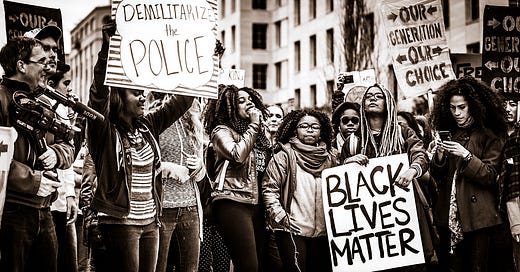

Last week, a panel of judges on the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit decided Doe v. Mckesson, a case that commentators and legal scholars have been tracking carefully. The facts involve a Black Lives Matter protest in front of the Baton Rouge police department. The protest was led by DeRay Mckesson, a movement leader for Black Lives Matter. Mckesson eventually led the protesters onto a local interstate to block traffic. At this point, Baton Rouge police began making arrests, and during this confrontation an unidentified protester struck and severely injured an officer.

Nobody disputes that the protester who struck the officer would be criminally and civilly liable for their actions should they be identified. The complication in this case arises because the officer also sued Mckesson. The officer argued that Mckesson had personally led the protest, had engaged in lawbreaking by obstructing traffic, and should be responsible for the officer’s injuries at the hands of another protester.

The panel opinion, authored by Judge Jennifer Walker Elrod, concluded that the First Amendment does not shield Mckesson from potential tort liability for the violent actions of the unidentified protester. Judge Don Willet dissented, arguing that the majority’s argument seems to be that Mckesson “negligently organized a protest.” Willet elaborated: “If negligence is not constitutionally protected, then I don’t know what would be.” And he warned of significant consequences that will follow from the court’s holding:

To spell it out, I am concerned that those who oppose a social or political movement might view instigating violence (or feigning injury) during that movement’s protests as a path toward suppressing the protest leader’s speech—and thus the movement itself.

The majority countered that “leaders are far more responsible for the organization’s operations and therefore have a closer connection to unlawful activities committed by its members” and concluded that states “may impose tort liability for unreasonably dangerous conduct.”

In My Head

I think the Fifth Circuit panel got this wrong. A few things stand out about Judge Elrod’s reasoning. First, she relies a great deal on Mckesson’s lawbreaking in blocking the interstate:

Given the intentional lawlessness of this aspect of demonstration, Mckesson should have known that leading the demonstrators onto a busy highway was likely to provoke a confrontation between police and the mass of demonstrators yet he ignored the foreseeable danger to officers, bystanders, and demonstrators, and notwithstanding, did so anyway.

Judge Elrod adds that Mckesson knew from his participation in other Black Lives Matter protests that police officers had been injured after confronting protesters who had blocked highways. She concludes that Mckesson “organized and directed the protest in such as manner as to create an unreasonable risk that one protester would assault or batter [the officer].”

The precise violation falls under La. Stat. Ann. § 14:97, which criminalizes “simple obstruction of a highway of commerce.” The law provides:

A. Simple obstruction of a highway of commerce is the intentional or criminally negligent placing of anything or performance of any act on any railway, railroad, navigable waterway, road, highway, thoroughfare, or runway of an airport, which will render movement thereon more difficult.

B. Whoever commits the crime of simple obstruction of a highway of commerce shall be fined not more than two hundred dollars, or imprisoned for not more than six months, or both.

Notice that while § 14:97 is a criminal provision, it is a relatively minor offense.

Blocking an intersection is a common protest tactic; it also occurs regularly when sports fans rowdily celebrate their team’s victory or concertgoers flood the streets after an engaging show. My family and I attended a recent Final Four in New Orleans, and had our team won, we may well have found ourselves in the streets in violation of La. Stat. Ann. § 14:97. I would hope in those circumstances that the team’s mascot would not be personally liable for ushering fans into the streets if one of them in a drunken stupor ended up injuring a police officer.

Judge Elrod also relies on a 1982 Supreme Court decision, NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware. The case involved decades of litigation arising out of boycotts by black citizens against white-owned businesses in Claiborne County, Mississippi. The boycotts were led by Charles Evers, field secretary of the NAACP. They were mostly peaceful but included some acts of violence over the course of several years. Evers never engaged personally in violent acts but “threatened violence on a number of occasions against boycott breakers.” The Supreme Court refused to hold Evers liable for the violent actions of boycotters against boycott breakers.

Judge Elrod sees “significant differences” between Claiborne Hardware and the Baton Rouge protest at issue in Doe v. Mckesson. She emphasizes that Evers “advocated for violence in general terms, but acts of violence did not follow until weeks or months after the speech at issue there.” She also notes that unlike Mckesson, who blocked the interstate, Evers himself had not created unreasonably dangerous conditions. Neither of these distinctions is constitutionally significant. First, the temporal proximity of violence to an expressive protest might be evidence of imminent incitement to lawbreaking, but the liability of a protest leader shouldn’t hinge on the unknowable timing of a protester’s independent actions. Second, as previously noted, Mckesson did not himself engage in any egregious behavior by breaking a minor law; if anything, Evers’ threats of violence make him more culpable than Mckesson’s nonviolent direction to block the interstate.

I hope Mckesson petitions for en banc review by the full Fifth Circuit or for certiorari to the United States Supreme Court. This is an important issue that deserves greater attention.

In the World

Law professor Timothy Zick is one of the country’s leading experts on the rights of speech and assembly. His most recent book, Managed Dissent: The Law of Public Protest, underscores the ongoing importance of protest to Americans: “between January 2020 and June 2021, there were more than 30,000 public demonstrations in the United States.” Zick highlights the longstanding tradition of protest in this country but cautions that it cannot be taken for granted:

As deep as these historical roots run, we ought not to take the continued vitality or even the existence of public protests for granted. Public and official attitudes toward protest have ranged from lukewarm to overtly hostile. Too often, governments have responded to peaceful public protests with aggression, escalated force, and other repressive tactics. There are myriad limits on where, when, and how protests can occur. Police enforce a bevy of broad and sometimes vague public disorder laws against public protest organizers and participants, who are also subject to significant costs and civil liabilities—sometimes for vandalism and violence they did not participate in or encourage.

Doe v. Mckesson is a timely reminder of the work that remains to be done to strengthen constitutional protections for public protests, and Managed Dissent is one of the resources that policymakers and judges can use toward that end.

Totally agree with you, John. I’ve been part of peaceful protests that involved blocking streets. It doesn’t necessarily lead to violence and much of that depends on how the police respond. I’ve even been part of protests where police blocked intersections to allow the protestors to march. Makes me wonder - according to this ruling could that even make the police culpable??

Excellent work, John. And thanks for plugging my new book!