Religious Freedom in a Pluralistic Society

Strong free exercise protections don't require public displays of religion

Although you might not know it from social media and partisan news, two major themes have unfolded in the Supreme Court’s religious liberty cases over the past decade. First, the Court has substantially strengthened protections for the free exercise of religion. Second, the reasoning and outcomes of these decisions have not followed typical culture wars splits.

In 2012, the Court unanimously held in Hosanna-Tabor v. EEOC that religious institutions can hire their ministers and leaders on their own terms, even when those decisions conflict with employment discrimination laws. In 2020, the Court expanded that doctrine, known as the ministerial exception, in a 7-2 decision, Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berru. In 2018, the Court sided 7-2 with Jack Phillips, the conservative Christian who did not want to make a cake for a gay wedding, in Masterpiece Cakeshop. In 2021, the Court unanimously held in Fulton v. City of Philadelphia that a city could not exclude Catholic Social Services from among the agencies it uses to contract for foster services.

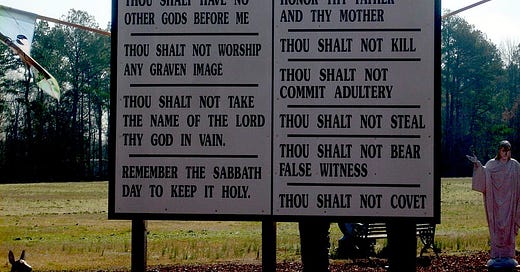

Despite these developments, some religious conservatives still see themselves on the losing end of the Court’s approach to religious freedom. Their baseline appears to be the 1950s and 1960s, when Ten Commandments monuments were popping up around the country and prayer—of mostly a Protestant variety—was still permitted in public schools. For these conservatives, important religious freedoms have been lost in recent decades and need to be regained.

In the News

Last week, the Texas Senate passed two controversial bills backed by religious conservatives. One requires public schools to post copies of the Ten Commandments in every classroom; the other allows “public and charter schools to adopt a policy requiring every campus to set aside a time for students and employees to read the Bible or other religious texts and to pray.”

Following the passage of these bills, Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick issued a statement lauding their goals:

Allowing the Ten Commandments and prayer back into our public schools is one step we can take to make sure that all Texans have the right to freely express their sincerely held religious beliefs. I believe that you cannot change the culture of the country until you change the culture of mankind. Bringing the Ten Commandments and prayer back to our public schools will enable our students to become better Texans.

Meanwhile, the Texas Senate is scheduled to vote soon on a third bill that would allow public schools to provide chaplains. That bill’s sponsor called the separation of church and state “not a real doctrine.”

In My Head

It’s hard to dismiss the news out of Texas as mere rhetoric—this is the senate and the lieutenant governor of the second largest state in the country. On the other hand, modern religious liberty law has made clear that the Ten Commandments cannot be posted in public school classrooms (Stone v. Graham) and public schools cannot offer prayers (Engel v. Vitale) or Bible readings (Abington v. Schempp). Similarly, while the scholarly field of law and religion has grown increasingly fractured in recent years, almost nobody writing in this field argues that the Ten Commandments or prayers should be back in public schools. Even if these practices once made sense in a more homogenous society, changing demographics have made this country far more religiously diverse, including substantial numbers of nonbelievers.

Apart from their legal implausibility, efforts like those out of Texas rely on questionable rhetoric. Proponents invoke the “Judeo-Christian tradition” to suggest that Christians and Jews alike would be eager to see civil religion or a shared morality reinforced through displays like the Ten Commandments. One problem with this argument is that there just aren’t many Jews in the regions of the country where the Judeo-Christian tradition is most often invoked. In Texas, for example, Jews comprise a whopping 0.6% of the population. Tellingly, the Texas bill requires the text of the Ten Commandments to come from the King James Version of the Bible, not exactly the preferred translation of a certain 0.6% of the population in Texas.

A religiously pluralistic society should offer strong protections for religious freedom, and the Supreme Court has increasingly done so in recent years. But robust religious freedom neither requires nor implies uninhibited public displays of religion.

While the Court is not going to bring back school prayer or allow the Ten Commandments to be posted in public school classrooms, it has sometimes failed to appropriately limit religious expression by government officials in public settings. Consider, for example, the Court’s 2014 decision in Town of Greece v. Galloway, which involved an invocation delivered by local clergy before town board meetings. The Court upheld the practice as constitutionally permissible under the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause.

Justice Elena Kagan’s dissent made the better argument. Kagan illustrated the implications of the prayers with a thought experiment drawing from the record before the Court:

You are a party in a case going to trial; let’s say you have filed suit against the government for violating one of your legal rights. The judge bangs his gavel to call the court to order, asks a minister to come to the front of the room, and instructs the 10 or so individuals present to rise for an opening prayer. The clergyman faces those in attendance and says: “Lord, God of all creation, . . . We acknowledge the saving sacrifice of Jesus Christ on the cross. We draw strength . . . from his resurrection at Easter. Jesus Christ, who took away the sins of the world, destroyed our death, through his dying and in his rising, he has restored our life. Blessed are you, who has raised up the Lord Jesus, you who will raise us, in our turn, and put us by His side. . . . Amen.” The judge then asks your lawyer to begin the trial.

For Kagan, these prayers “express beliefs that are fundamental to some, foreign to others—and because that is so they carry the ever-present potential to both exclude and divide.”

So, too, do the recent efforts out of Texas.

In the World

Many of the themes of today’s post call to mind the work of Doug Laycock, one of the foremost scholars of law and religion. Doug has also argued a number of important cases before the Supreme Court. Currently a law professor at the University of Virginia, he will retire next month after four decades of teaching law.

Anyone looking for a deep dive into the world of law and religion would benefit from Professor Laycock’s five-volume treatise. Those with more modest ambitions might start with this tribute to him published earlier this week.

Professor Laycock has been a consistent advocate of religious freedom, taking seriously both the claims of religious believers and the importance of tempering religious zealotry in a deeply divided society. He will retire to Austin, Texas, where he taught before arriving at the University of Virginia, and where I hope he will have ample time to take on the Texas Legislature.

Thanks, John. As a Southerner, I feel like I have a bit clearer perspective on "cultural Christianity," where being white, well-educated, and typically leaning to the right side of the isle automatically means I'm a Christian. They're one and the same. The same people who assume this is true would also be the sort to long for the "good ole' days" when we had prayer in schools and the 10 Commandments publicly displayed. For quite a long time, I dismissed this as part of the background noise of my upbringing. However, one of my secular friends changed my perspective. This friend told me that he hopes that we return prayer in schools, etc. He's British, and he says that the state's "religious" schools have made religion all together irrelevant in England, because it's part of the state. In his mind, the quickest way to "secularize" America is to turn religion into a secular thing. I tend to think he's right. I also have been in education long enough to know that we tend to "formalize" everything in our public schools, and that causes me to fear what kind of prayers would be spoken, and I cringe to think about the way curricula would talk about the 10 Commandments. I am thankful for our religious liberty and deeply appreciate those who fight for it; however, any talk of putting prayer or the 10 Commandments into our public schools gives me profound concern.

Thanks, John. This Texas news goes right along with the “ separation sentiment” so prevalent in that state.