The Decline of the Protestants and the Rise of the Nones

The importance of religion may be declining, but what does it mean and where are we headed?

This past week, my undergraduate seminar on Law, Religion, and Politics read Joseph Bottum’s An Anxious Age: The Post-Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of America. Bottum argues that “The single most significant fact over the past few decades in America—the great explanatory event from which follows nearly everything in our social and political history—is the crumbling of the Mainline churches as central institutions in our national experience.”

Bottum contends that mainline Protestantism (by which he means mainline white Protestantism) provided a social and cultural glue for the country and that its rapid collapse has left a significant void in our national ethos.

According to Bottum, the only group with enough social and cultural capital to replace the Protestant mainline is what he calls “Post-Protestantism,” which refers to a generally non-religious and politically liberal demographic. Although Bottum’s Post-Protestants do not completely align with the “nones” (which Pew Research Center describes as a shorthand “to refer to people who self-identify as atheists or agnostics”), there is sufficient overlap to equate them for purposes of this post.

In the World

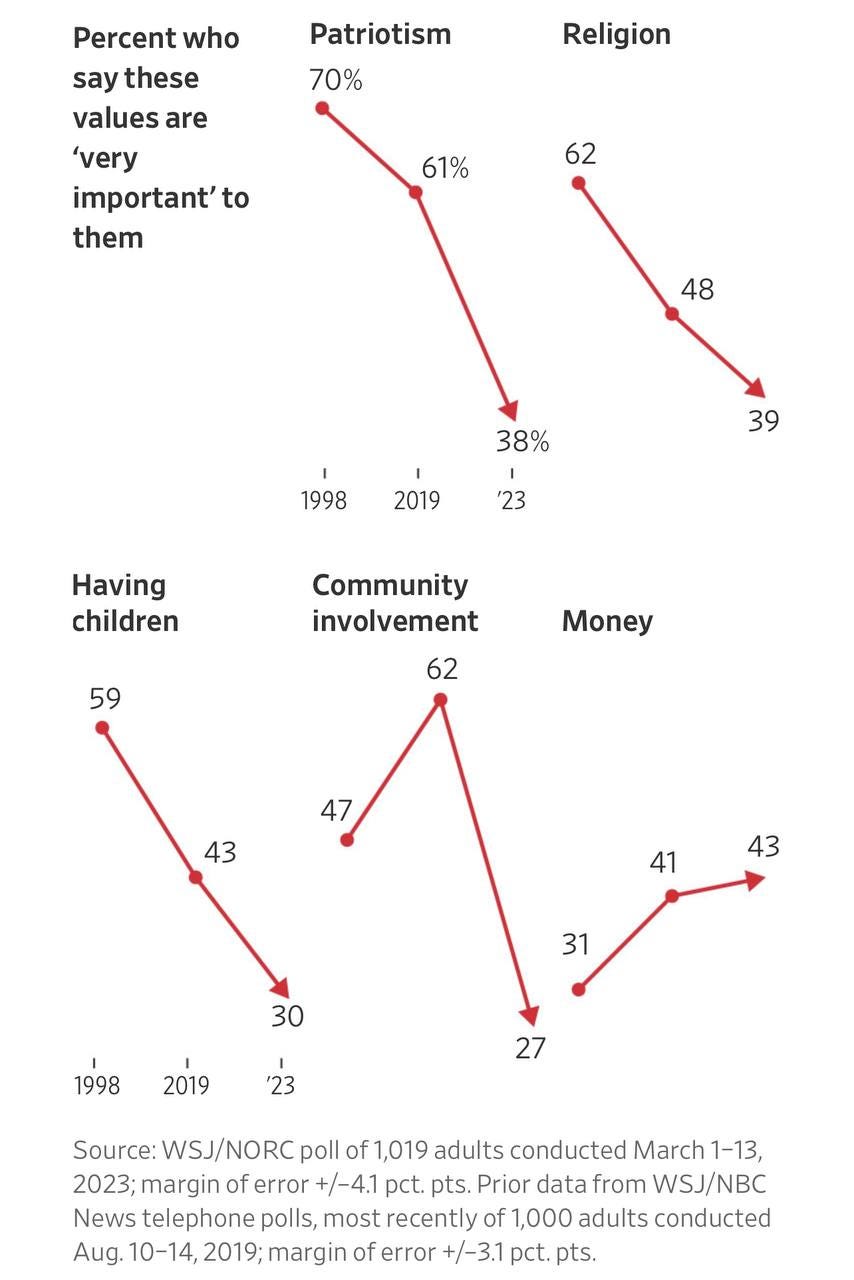

Last week, the Wall Street Journal caused quite a stir reporting on a new poll indicating plummeting interest in patriotism, religion, having children, and community involvement. Here is the version of the poll results that made the rounds on Twitter:

The chart reflects the poll’s finding that the only interest that increased among survey respondents from 2019 to 2023 was making money.

As Patrick Ruffini cautioned, the chart was “destined to go viral” and probably overstates the relative decline. Among other things, the survey’s methodology changed from phone to online polls between 2019 and 2023. Ruffini elaborates on the significance of this change:

The basic idea is this: if I’m speaking to another human being over the phone, I am much more likely to answer in ways that make me look like an upstanding citizen, one who is patriotic and values community involvement. My answers to the same questions online will probably be more honest, since the format is impersonal and anonymous. So, the 2023 survey probably does a better job at revealing the true state of patriotism, religiosity, community involvement, and so forth. The problem is that the data from previous waves were inflated by social desirability bias—and can’t be trended with the current data to generate a neat-and-tidy viral chart like this.

Not everyone picked up on the methodological nuance. Writing in The American Conservative, Bradley Devlin blamed the “political elite class” that has been arguing “Americans shouldn’t love America.” Brownstone Institute President Jeffrey Tucker told Fox News that the poll reflected present trends that, left unaddressed, could signal “the end of the American empire.”

In My Head

I share Ruffini’s suspicion that the conservative reaction is overblown and the Journal’s poll likely overstates the relative decline. But if we zoom out to a longer time horizon, it seems reasonable to conclude that the importance of patriotism and religion has substantially declined in recent generations. Americans are less religious than ever before. And when it comes to patriotism, the lack of a clear ideological enemy (like that which animated the Cold War) and a decrease in the size of the armed forces might reasonably bring a decline in patriotic commitments.

More significantly, the Journal’s numbers risk hinting at the wrong political lessons. Look back at the results on the importance of religion. In 1998, 62% of Americans thought religion was very important and only 39% of Americans think it’s very important today. One might be tempted to assume a trend and conclude that the percentage of Americans who think religion is very important will continue to shrink to 10% or less in the coming decades. That demographic reality would begin to approximate an inversion of the United States in the 1950s, at the peak of the Protestant consensus in which Bottum anchors his analysis.

But my hunch is that immigration trends (with immigrants often representing some of the most religious Americans) and other factors make this outcome extremely unlikely. The importance of religion may be declining, but religion in America is not heading toward extinction, and we are likely to see the rate of decline decrease over time. I have no idea what the eventual number might be, but for argument’s sake, let’s assume that in the coming decades roughly 30% of Americans will consider religion “very important.”

If I’m right about the future demographic reality, then even if Bottum is right that the nones have assumed the mantle of the Protestant mainline, they will face a much different political challenge. In the 1950s, over 95% of Americans were part of some religious tradition, which means the nones at most hovered around 5% of the population. They were a true minority, which meant that the Protestant mainline could assume its own values and language in cultural commentary, political campaigns, and moral crusades. Think, for example, of the political efficacy of the phrase “Judeo-Christian,” which rose to prominence in the mid-twentieth century.

Religious believers will not be a minority in the same way the nones were under the Protestant mainline. That means the nones will not be able to assume shared values and language—their ideas will resonate inside their own social circles, but they won’t consistently win elections or unify the country. In other words, the nones will still need to translate their ideas and build coalitions rooted in compromise and common ground values. This is a much different political context than the Protestant mainline of the 1950s.

In the World

It seems appropriate in this post to recommend Bottum’s An Anxious Age. One of Bottum’s most important insights is that today’s nones, like their Protestant mainline predecessors, see themselves “on the right side of history” and tasked with stewarding the country toward its future. But the nones have one significant difference from the mainline: they lack an eschatology (a final account of the soul and humankind). One need not embrace the substance of a Christian vision of the future to recognize that it names a direction and end that orders its values. A directionless alternative will have much greater difficulty naming and sustaining its core values in the decades to come.

Immigration could certainly be a mitigating factor in the rate of decline; another is that believers and immigrants tend to have more children and both are more apt to raise their children with a respectful attitude to tradition and religion. On the other hand, the US educational establishment – in public schools, upper-class private schools, and nearly all colleges – is adamantly, and all but universally, opposed to both tradition and religion.

As a none raised in and among Protestants I am often puzzled about the lack of religious study in and among American historians, a field adjacent to your own. I am glad to read about Bottum's work in this regard. His thesis seems to me central to understanding the American scene. It is also true that nones lack an eschatology, a narrative of meaning beyond the individual grave and a timeless human governmental experience in a natural environment. Following Yuval Harari I hope not for an unending meaning narrative for myself or the human commune. I work alone and with others to mitigate suffering in the present. I hope for the mitigation of suffering in the future.