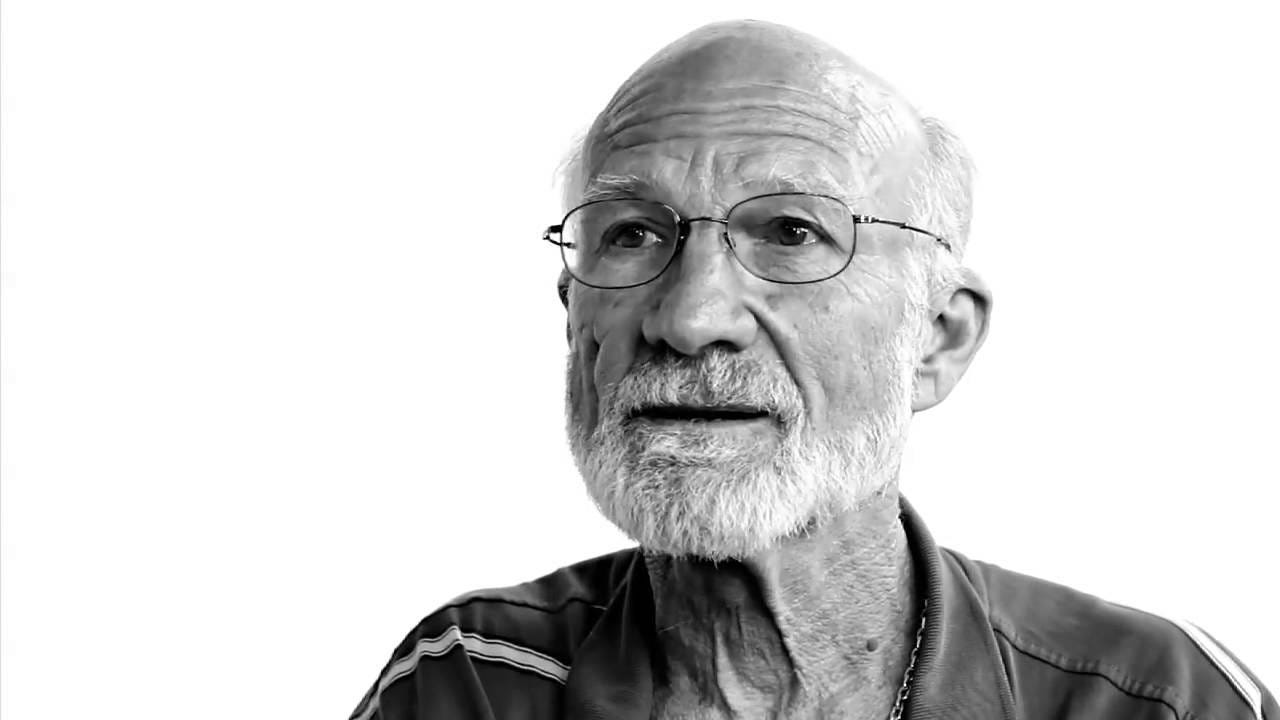

My Q&A with Theologian Stanley Hauerwas

A discussion of law, theology, and other topics with my teacher and friend

Few people have influenced my intellectual development more than Stanley Hauerwas. As a law student in the late 1990s, I audited his class on Christian Ethics in America. Then, after four years working as a military attorney at the Pentagon, I returned to graduate school and took more classes with Hauerwas. He served on my dissertation committee and took time to meet with me outside of classes, including a summer we spent reading Wittgenstein together. (Those of you familiar with Hauerwas’s writing and pacifism will know that sandwiching my Pentagon service with his influence was not uncomplicated for me.)

Shortly after I began teaching, I convened a symposium connecting Hauerwas’s work to legal and political theory. That symposium, published in Duke’s Journal of Law and Contemporary Problems, includes what I think may be some of Hauerwas’s most direct commentary on law and legal practice. For example, in his response to the symposium essays, he wrote that law “may at times be violent, but power can also often be an alternative to violence.” He added: “The law is a morally rich tradition that offers a language otherwise unavailable for the conflicts we need to have as a society. That is a tradition in which I should like to count myself a participant.”

Stan has become a generous friend and conversation partner, and it was a privilege for me to engage him in a dialogue for this special edition of Some Assembly Required. We began with some complex questions about the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre and the differences between law and war. I’ve edited our discussion for length and clarity, but the technical nature of our first few questions may still be difficult to follow if you’re unfamiliar with MacIntyre or you’re reading this before your morning coffee.

John Inazu: Thanks for taking the time to talk with me today. Let’s jump right in. I think I first read MacIntyre through you, and I don’t think I’ve ever seen the world the same since then. Through MacIntyre, I’ve come to understand how people form and are formed by habits and practices that unfold within institutions. But I’ve never quite understood what to do with practices that are unintelligible across institutions. What do we do when we have been shaped by such wildly different institutions that we can no longer speak to or understand each other?

Stanley Hauerwas: Alasdair is not going to give you an easy way to respond to that kind of question—the question of what to do when you’re caught in incommensurable narratives. It is not by accident that he uses the language of “fragments” to start After Virtue because it defeats the description that we live in a pluralist world. Pluralism is the ideology of those who assume they’re standing somewhere that they can call everything else pluralism except where they’re standing. MacIntyre requires an ongoing close attention to language in a way that we might find some fragments that will not be destructive. But he cannot guarantee it.

JI: I’m not following your definition of pluralism. Why couldn’t I embrace pluralism as a recognition of my own epistemic limitations, without surrendering claims of what constitutes reality, just knowing that I'm not always going to be able to translate my viewpoints successfully?

SH: The crucial word you use there is translate. Go back and look at those passages in Whose Justice? Which Rationality? where MacIntyre takes on the notion of translation. For MacIntyre, you can translate sentences, paragraphs, and even books. But you can’t translate everything. MacIntyre gives the example of Londonderry in Northern Ireland. The Irish Catholics called it Doire Columcille in Gaelic. And Londonderry doesn’t translate to Gaelic. So what the Irish have to do is try to kick out the English, because translation is not possible. This is where there’s a deep difference between MacIntyre and myself. MacIntyre cannot rule out the possibility of war because on his account communication will become impossible, and war is oftentimes necessary. As a Christian, I’m against war. Part of what it means to be a follower of Christ in the world in which we find ourselves is that you will oftentimes have to endure your enemy’s control of you. At the point at which translation seemingly becomes impossible, you endure rather than fight.

JI: Let’s then talk about the relationship of this claim to the law. I’ve been persuaded by Robert Cover’s Violence and the Word that the law, like the military, ultimately rests on the use or threat of violence. How do you distinguish between law and war?

SH: Law is delayed violence as long as one can endure. So the difference between law and war is that law allows a conversation across time and puts matters in context that provides possibilities of resolutions of conflict short of killing one another.

I have to say in terms of my own reflections about these kinds of things, the rise of the Christian Right has made me much more committed to the rule of law than perhaps I had been in the past. Because given January 6th, the rule of law looks damn good. I respect the time it takes to sustain the kind of adjudication of descriptions that makes the law what it is in terms of the creation of a fragile peace that is nonetheless better than killing one another.

JI: I take it your point is that in order to hold the rule of law, you need people using violent coercion to resist the people storming the Capitol. Who are those people who resist?

SH: People who are well trained and who know how to defuse the violence in a way that doesn’t necessitate killing.

JI: Let me switch gears to the topic of scriptural interpretation. I remember reading your book Unleashing the Scripture when I was in graduate school and being haunted by your claims about the individualistic ways that Protestants read the Bible. This has always worried me as someone who has moved around quite a bit and has been at different churches at different phases of life. Am I correctly understanding your argument? And if I am, is there a more hopeful possibility of how we read Scripture together?

SH: The Protestant mantra sola scriptura has legitimated Scripture scholarship that most Protestants no longer have to read Scripture with other Christians. They just have to say “what are the biblical scholars telling me I should believe that Scripture is saying?” Against that norm, it’s still very important that every Sunday there is a preacher who is to respond to the text assigned in a way that defies their subjectivity. There is a tradition across 2000 years of people reading Scripture in a way that makes those that are receiving it knowledgeable of what God has done. I’m not opposed in any way of people engaged in reading the Bible together in small groups. But there must be some institution that over time tests those readings. What the magisterium does for Catholics is not tell you “it must be read this way” but “look at all the wonderful readings we’ve narrated and don’t leave them out.” I’m on the Catholic side and the problem is that we Protestants don’t have a magisterium.

JI: I take it that this is part of what complicates a Christian Right rooted in nondenominational independent churches and personalities.

SH: The problem with evangelicals—at least one of the problems—is they think they have a relationship with God but church is optional. They don’t have any sense that without the church, there’s no salvation. You learn how to be a follower of Christ through the formation of your life in relationship to other lives. That’s called the church, and you don’t get to make up your mind about it.

JI: This makes me think back to MacIntyre. Isn’t the kind of evangelical nondenominational church now embracing the political Right also an institution—a set of people and practices that might understand themselves to be interpreting scripture together within the community they call church? How do you defeat that from the outside?

SH: You don’t. I don’t get why people go to hear Joel Osteen. I assume that those formations, which look to me like parodies of Christianity, cannot and will not sustain themselves. The people that are now going to hear Joel Osteen may work it out for the rest of their lives, but their children won’t go to hear Joel Osteen. And it’s a judgment on us that we don’t say that these people are simply shams.

JI: But who is the “we” who calls this out? You say that the children of the people attending Joel Osteen’s church won’t be there when they grow up, but I look around and wonder how many of the children attending our churches are going to be there. And when I look at the state of youth ministry and other trends, things don’t exactly look promising. So who is the “we” that makes those critiques with any moral authority?

SH: My sense is that God is making us leaner. You’re going to go to church when you need it to survive. And that’s what hopefully can be happening over the next 100 years. Christians don’t do short time. We’ll have to wait and see.

JI: And as we wait and see, what happens to academic theology and theological education?

SH: Duke Divinity School is doing what most seminaries are doing—admitting students who will be only in residence for very short periods because they will take courses by distance learning. But distance learning means there’s no formation. Our formation depends on exemplification and seeing what it looks like in relationship to real people. I think we’re in a really fragile time in terms of the kind work that needs to be done in terms of the teaching and formation of students who serve in ministerial roles.

JI: I’ve been reading Brad Kallenberg’s God and Gadgets. It’s about a decade old, but I actually think it’s still extremely prescient and relevant. One of his many important insights is to consider “the ways that technology has a monopoly on the ways Christians see the world.” I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately in light of the current and coming revolution in artificial intelligence. How do you think Christians ought to be preparing for this next wave of technology, and what practices will we need to develop?

SH: Let me respond to this personally. Paula and I have discovered that we are not welcome in the digital world. We don't know how to negotiate it. The influx of the digital world means that those of us that are older are now confronting a world we cannot act in. For example, we had our television go out. You can’t buy a new TV. You have to buy a smart TV. And then we can’t figure out how the hell it works. That’s just a minor example.

My father was raised in Commerce, Texas, and he had to ride a horse to school. I wasn’t terribly sympathetic as he told that kind of story about his growing up and what it meant for him to transition into a world dominated by the automobile and learn how to negotiate that world. But now I wonder about how technology creates power for certain generations and disempowers other generations.

JI: What’s so interesting about what you just said about generational disempowerment is that the younger generations who are most adept at the new technology are also the least experienced in life. They will be increasingly disconnected from older generations who have more life wisdom. So I suppose one question for Christians is trying to reimagine what intergenerational friendship and codependence might look like.

SH: Yes, this is a MacIntyrean point, too. The loss of a sense of narrativity and its crucial character for the formation of our lives as good lives means that the elderly no longer are expected to have a responsibility to be wise. And that is a deep loss. When you have the responsibility to be wise, it means you have to know the determinative narratives that shape our lives.

JI: You’ve spent your career straddling the two worlds of university and church, and that is also where I find myself. What have you learned about yourself from being immersed in these worlds for so long?

SH: I have loved the academy. It is such a privilege to be able to read books. But I can’t imagine that I could have survived the academy if I hadn’t been first and foremost a Christian. I love the tensions between church and university and the people that are produced in both.

Those interested in an introduction to Stanley Hauerwas’s work might start with The Hauerwas Reader.

Thanks, John. Hauerwas always worth listening to. But his admission that 6 January made him more committed to the rule of law than before is kind of telling of a significant blindspot in his political thinking. Wasn't there abundant, overwhelming evidence, pretty much everywhere in the world not least the USA, of the indispensability of the rule of law as a non-negotiable minimum benchmark of

a stable and just society (however imperfect its practice) long before this? I'll keep reading him anyway!

I've been frustrated by what I perceived as Hauerwas' influence on practical political theology over the years (put very simply as a kind of withdrawal from political life). This interview suggests that he's been misinterpreted. "Endurance" is not withdrawal but rather a particular kind of connection that is powerful in its own way.