Learning from Failure

Success for most people doesn't come naturally--or at least not without failure

Earlier this month, I highlighted a day I spent with a group of medical professionals at Mayo Clinic. One striking aspect of the formal and informal discussions were references to publicly sharing failures. For example, one medical school holds an annual session where senior physicians share their failure stories, which often resulted in the deaths of patients. At dinner, another physician shared a similar session that takes place at his annual specialty conference.

It occurred to me that other professional circles could probably benefit from their own “failure sessions.”

In the News

Last month, Jancee Dunn wrote a New York Times newsletter about failure as a precondition to thriving. Dunn interviewed Amy Edmondson, a professor of leadership at Harvard Business School, who suggested that we can learn from our missteps if we put our failures in context, learn how to pivot, and encourage sharing our failures with others. Dunn adds:

In the spirit of failure sharing, here are a few of mine. I flunked the test to get my driver’s license three times. I was fired from Burger King for not filling sodas fast enough.

And, as an author, I have done several readings where no one showed up. At my last one, a man wandered in and sat in one of the empty chairs. After a few more minutes of waiting in vain for more people, I asked the man if he’d like me to begin my reading.

He explained that he was sitting there only because his feet hurt. “Actually,” he said, “I’d prefer that you didn’t read.”

At the same time, there’s a difference between people who fail but ultimately succeed and those who those who do not overcome failure. As an article in the Scientific American noted a few years ago, “the people who eventually succeeded and the people who eventually failed tried basically the same number of times to achieve their goals. It turns out that trying again and again only works if you learn from your previous failures.”

In My Head

Speaking with the medical professionals at Mayo, I was struck by how countercultural it is in medicine—or law—to highlight failures. Professionals in both settings would much rather project strength and competence than admit that most people, even highly successful people, encounter their share of failures. But this tendency is shortsighted for at least two reasons. First, younger professionals are inculcated into a world that hides or downplays failure rather than one that normalizes it. Second, as most successful professionals will tell you, there is a lot that can be learned from past mistakes.

I recently participated in a small dinner of writers and institutional leaders. As we began our time together, I invited each person to share with the group an experience of either a challenge or a failure. Everyone in the room shared a failure. The collective experience of hearing these stories was profoundly moving, and it connected us far better than if we had all shared challenges.

There is a bit of an art to sharing real failure stories. You should avoid the urge to mask hero stories as failure stories—the narratives of tricky or even embarrassing situations where you look good in the end. We’ve all seen these self-serving narratives akin to The Office’s Michael Scott admitting his greatest weaknesses: “I work too hard, I care too much and sometimes I can be too invested in my job.”

You should also distinguish failure stories from victim stories. The setbacks from these two kinds of stories may be similar, and people can learn from both kinds of situations. But failure stories are more about how you have fallen short rather than how others have fallen short or have wronged you.

My own areas of legal practice and law teaching have not typically placed me in positions where lives are on the line in the way that some of my colleagues in the medical profession have encountered. Still, the performance pressures of the legal profession can make it difficult to discuss failures.

I’ve recently shared one of my failure stories—my misguided attempt to fill out the Faculty Appointments Register the first time I entered the law teaching market. In the spirit this post, here are a few other failure stories:

Misunderstanding the opening argument

The very first legal proceeding I ever argued was a military discharge hearing the summer after my first year of law school. I was a twenty-three year old second lieutenant interning in an Air Force legal office. My assignment was to make the opening argument in the government’s case against an individual being discharged under other than honorable conditions. Because this was my first argument, I practiced my opening before the attorneys in my office. They gave helpful feedback about how to improve my argument and reminded me that the formal rules of evidence did not apply in this proceeding. One colleague cautioned me that the defense counsel might object to something I said about three minutes into my argument. If I received an objection, I should turn to the judge and begin to explain why the objection was unwarranted.

The actual hearing began something like this:

2nd Lt Inazu: “May it please the court, this airman maliciously . . .”

Defense Counsel: “Objection. Argumentative.”

2nd Lt Inazu: *begins turning toward the judge to argue against the objection*

Judge: “Objection sustained.”

2nd Lt Inazu: *uncomfortably prolonged silence*

Co-counsel for the Prosecution: “You can go on, Lieutenant.”

In hindsight, the whole experience reminds me of a scene from the movie A Few Good Men when Kevin Pollack’s character berates his junior co-counsel (played by Demi Moore) for “strenuously objecting.” It’s also one of the reasons I am today cautious with adverbs in my speaking and writing.

Jumping the gun on graduation

After legal practice, I returned to school for graduate work in political science. Although I had five years of funding for my PhD, I was able to finish the program in four years. I proudly submitted my dissertation and completed the other graduation requirements. My wife and I welcomed our second child, Hana, a few weeks before graduation, which is about when I realized that graduating would mean no stipend and no health insurance. And, I should mention, I had no job prospects, a mortgage, and now four mouths to feed.

Looking back, the smarter path would have been to delay graduation and keep the funding and benefits that came with my program. It was a significant oversight that led to a great deal of family strain and the need to find a way to pay the bills. Eventually, I took an hourly job at a law firm performing low-level litigation support. Before graduate school, I had supervised complex litigation efforts at the Pentagon with hundreds of millions of dollars at stake. Now a few years and one PhD later, my haste to finish my studies had placed me in far different position. Had I taken the time to account for the next year instead of just the next few months, I might have avoided the situation.

Teaching the case backwards

One of the courses I have taught in law school is first-year criminal law. I described an early mishap with this course in the chapter I contributed to my edited volume, Uncommon Ground: Living Faithfully in a World of Difference:

During my first year of teaching, I misread one of the cases in my criminal law class and thought it stood for exactly the opposite of what it said. This was the law school equivalent of explaining multiplication when you think you are explaining division. And because I had built my entire lesson plan around my misreading of the case, the more I tried to explain my incorrect understanding, the more confused the class became.

This was perhaps my lowest professional moment—a public embarrassment in front of first-year law students who were looking to me to teach them about the law.

The most apparent lesson from this failure episode—don’t teach the wrong things—is not exactly insightful. But I think the experience of that failure also gave me a lot more grace for other teachers—including those who have taught me, teach alongside me, and will teach after me.

Like all of us, I also have more personal stories of failure in my relationships with other people. Those are better shared in smaller, less public settings. But they are worth sharing. Normalizing personal as well as professional failures is normalizing what it means to be an imperfect human being.

Of course, it’s far easier to share failures when you have some distance from them or when you have overcome or otherwise addressed them. The failure stories I’ve shared here are all in the distant past. Jancee Dunn’s story about her lonely book reading may still be a painful memory, but there’s undoubtedly some consolation that she’s writing about it in the New York Times.

I don’t think there’s any recipe for when, with whom, or how to share failure stories. But I do think we should be sharing them, and learning from them.

In the World

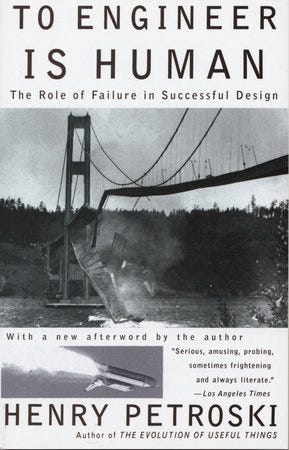

This week’s recommendation is Henry Petroski’s To Engineer Is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful Design. Professor Petroski was one of my teachers at Duke, where I majored in civil engineering. We read parts of this book in one of my classes with him.

Petroski explores some of the most infamous engineering design failures, including the collapse of the walkways at the Kansas City Hyatt Regency Hotel in 1981 and the destruction of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge in 1940. One of the book’s takeaways is that “behind every great engineering success is a trail of often ignored (but frequently spectacular) engineering failures.”

It’s a lesson applicable to all walks of life.

Thanks for your vulnerability. It's an example for others, myself included.

I have no idea what you are talking about… ahem…