The Pitfalls and Perils of Faculty Hiring

Reflections on the complexities of the academic job search

I am currently serving on our law school’s faculty appointments committee. This means I spend a substantial amount of time reading faculty candidate materials, interviewing candidates, and helping coordinate campus visits for finalists. (Having served in the past both as a member and chair of this committee, I am grateful that this year’s chair is my friend and colleague, Adrienne Davis—aka not me.)

Over the past few weeks, I have been thinking more broadly about the politics around faculty hiring as I’ve made final edits to my new book, Learning to Disagree. In one chapter focused on the question of what we do when compromise isn’t possible, I poke fun at what can transpire during the hiring process. The zero-sum nature of faculty hiring—a limited number of positions that can only address so many curricular needs—can lead to heated and sometimes amusing deliberations. You’ll have to read the book to get the details, but it’s fair to say that faculty—like most people—can easily conflate the institution’s priorities with their own.

The intensity and occasional absurdity of faculty hiring has caused me to reflect a bit about the current academic job market and my own past experiences with it. One important piece of context is how relatively few jobs there are, which raises the stakes and competitiveness of faculty searches.

In the News

According to the latest report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the United States will likely see almost 120,000 open faculty positions for postsecondary education (beyond the high school level) each year between 2022 and 2032. That sounds like a lot of jobs, but a more granular focus paints a different picture, particularly at the intersection of faculty jobs that I know best: (1) tenure-track positions; (2) in law or the humanities.

Last month, Inside Higher Ed reported that the number of history faculty positions has been “lethargic but stable” since 2016. But the article highlighted a significant drop in the number of tenure-track positions, with 274 openings this year compared to a median of 316 positions since 2016.

The numbers of faculty positions in philosophy appear to be similar, with a recent report indicating an average of 238 permanent job placements each year from 2013-2023.

Meanwhile, last year’s hiring cycle saw 129 entry-level tenure-track faculty hires by American law schools.

The bottom line is that the number of tenure-track faculty positions in law and the humanities is fairly small. And while many part-time and full-time faculty positions outside of the tenure track can be stable and rewarding, others can be financially challenging or even exploitative.

In My Head

One of the benefits of being jointly appointed in our law school and in the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics is participating in faculty searches in both law and other disciplines. The credentialing, hiring, and tenuring standards differ significantly by discipline, and it has been useful to see the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches. But since my own experience on the entry-level market was with law, I will focus here on that process but will tailor my comments to a general readership.

My experience with the teaching market has been a mixed bag. When I was completing my graduate work in political science, I threw my hat in the ring for law teaching—without consulting any law professors. I had no idea what I was doing, no idea of the disciplinary norms, and nobody within academic law advising me. One could characterize that first effort as less than successful.

The second time around things went much better. But it was only through the kindness and coaching of a number of senior colleagues, most especially Guy-Uriel Charles, that I had any sense of what to do. And even then, in that process and in the years since then, I have encountered my share of setbacks and frustrations with faculty hiring.

With this background, let me offer three suggestions to those seeking faculty positions and those hiring for those positions.

Learn the Inside Baseball

Every academic discipline has a set of unstated norms and customs. With rare exceptions, you will have to learn these discipline-specific norms and customs to have any shot at being a serious candidate. For example, if you are applying for a tenure-track humanities position at a major college or university, you’ll need to have a PhD, strong academic references, and substantial evidence of the ability to publish serious scholarship. The credentials for law teaching differ, but they are similarly inflexible. These days, you aren’t likely to be considered for a law faculty position without having substantial legal scholarship published or drafted that will be scrutinized by hiring committees.

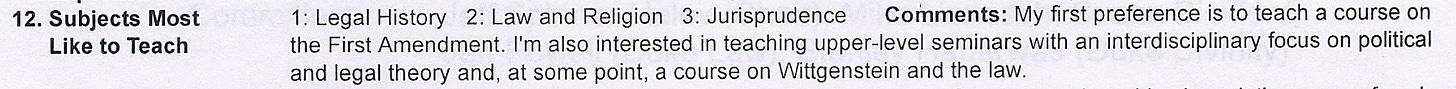

Beyond the substantive requirements, each academic discipline has its own language and procedures. In law, for example, almost all faculty candidates complete a form on something known as the Faculty Appointments Registrar (the “FAR Form”). One of the questions the FAR Form asks is which classes a candidate would most like to teach. The first time I completed this form, I assumed that the question wanted me to list my teaching interests. It turns out that the question is actually looking for classes: (1) credibly related to your background; and (2) that schools will likely need for curricular coverage. Typically, a candidate would list one or more first-year courses (like torts or contracts) or high demand upper-level courses (like corporations or administrative law).

Because no law professor or law faculty candidate would believe my actual answers, here is a cropped picture of that section of my FAR Form that year:

Among many other deficiencies to my approach, it’s fair to say that most law schools are not prioritizing their hiring around candidates interested in teaching a course on Wittgenstein and the law.

Try and Try Again, But Always Have a Backup Plan

Nobody likes to fail, but lots of people fail on the academic market. I did. And some of the smartest and most accomplished colleagues I know did, too. Sometimes you have to navigate the process more than once to understand how it works and how to bring your best effort. Sometimes you’ll have to endure embarrassing and vulnerable moments along the way. Sometimes you’ll finish just out of the running for your dream job.

At the same time, I think it’s wise to have a backup plan if the academic job doesn’t work out. Look again at the relatively few full-time jobs available in law and the humanities. Obtaining the minimal credentials for these jobs will get you into the pool of potential candidates, but there’s still a lot that can go awry between the start of your candidacy and a job offer and acceptance.

In my own case, after striking out during my first attempt on the law teaching market, I found myself jobless without any income or health insurance and my second child on the way (all of this is another story for another time). I found my way to a boutique litigation firm doing fairly mundane legal work where I was paid by the hour. It was not a very glamorous season of my life, but it paid the bills and gave me the opportunity to try again.

It’s good to have a backup plan. And even as you pursue a position with everything you’ve got, remind yourself along the way that these jobs do not amount to everything you are.

Be Kind, Always

This last point is directed toward everyone in the hiring process. If you are a candidate, be kind to everyone you meet, from students to faculty to faculty assistants. Nobody wants to hire a jerk.

And if you are interacting with faculty candidates, don’t forget how uncertain and unsettling this process is for them. Most of them are balancing not only career aspirations but also complicated personal circumstances. It is easy to treat a candidate’s job talk or small group interview as just one more administrative burden in an already busy week. But most candidates have invested substantial time and emotional energy preparing for their visit—the least you can do is give them a few minutes of your time.

If you are part of a hiring committee, keep people informed as best you can, be transparent, and be honest. I am fortunate to work alongside colleagues who take seriously these considerations and who remember the human dimensions underlying the candidacies you are considering. But in my experience, that is not always the case.

Learn the inside baseball, have a backup plan, and always be kind. On reflection, I think this advice probably applies beyond the academic job market to job interviews more generally. I hope that at least a few of you working in other sectors have found it helpful.

In the World

I realize that today’s post was a rather niche topic that’s likely not applicable to most readers of Some Assembly Required. I decided to write it because of the number of inquiries I receive from graduate students and aspiring faculty and the relative lack of information about the nature of faculty hiring, especially from a more general cross-disciplinary perspective.

For the rest of you who have stayed with me through this post, today’s recommendation is topically related but more generally applicable: Julie Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members. Schumacher explores the ebbs and flows of “a beleaguered professor of creative writing and literature at Payne University, a small and not very distinguished liberal arts college in the midwest.” Not unlike the short-lived Netflix show The Chair, Schumacher’s book highlights some of the absurdities of the liberal arts, including its hiring process. Dear Committee Members also offers a creatively unique format: the entire book is a series of (mostly) recommendation letters penned by Schumacher’s protagonist. And it is extremely funny. As a 2014 NPR review noted, “Like the best works of farce, academic or otherwise, Dear Committee Members deftly mixes comedy with social criticism and righteous outrage. By the end, you may well find yourself laughing so hard it hurts.”

I loved Dear Committee Members.

John,

It's tangential to though implicit in your post that the pursuing a career in academia as a liberal arts is a reasonable endeavor for someone who has aptitude and interest in it. I would argue that it's not clear that such a pursuit is a reasonable endeavor.

I would not argue that such aspirations are ignoble. Rather, I would simply look at the numbers and trends and question the likelihood of success. As you point out, there are not many new positions open annually. There are only so many students that are in a position to learn a given subject, particularly in a subject like law in which the bar to enter is high. Faculty can teach well into their 60s and 70s, so there aren't too many leaving the field in a given year. I would expect the number of new faculty positions to only decrease over time, as education increases in efficiency - efficiencies in education have been slow to develop, but with the advent of MOOCs and the like, the number of students that can be taught per professor has been on the increase, especially for entry-level lecture-style courses.

In some ways, pursuing a career as an academic in the humanities is like pursuing a career in the NFL, with the notable differences of a longer career (leading to less turnover), less widespread fame, and fewer traumatic brain injuries. I wouldn't recommend to even a really good high school football player to pursue a career in the NFL without a *significant* Plan B. Likewise, for those considering a career in academia, I would suggest, in the least, mapping out an alternative, in the more than likely event that Plan A doesn't pan out for you.

Unless you're John Inazu, the Fletcher Cox of Constitutional law.