Forgiveness, Part IV

How do you forgive someone you've never met or whose identity you'll never know?

Last year, I published a series of posts about forgiveness. My first post examined the possibility of forgiving friends and family whose pandemic choices conflicted with our own. After some strong reactions to that post, I followed up with a second on the importance and incomprehensibility of forgiveness. My third post featured an interview with Tim Keller about his book, Forgive: Why Should I and How Can I?

Today, I return to the topic of forgiveness to explore how it relates to people we won’t ever confront directly.

In the News

Writing at the end of last year in The New York Times, Tim Keller examined the question of “what too little forgiveness does to us.” Keller wrote that “a society that has lost the ability to extend and receive forgiveness risks being crushed by the weight of recriminations and score settling.” He counseled, “We should forgive because it is profoundly practical.”

But can we forgive someone we don’t know?

Last month, law enforcement officials in Tacoma, Washington, updated the city on the unsolved murder of Jordan Patterson, who had been found shot to death in December 2021. Following the update, Patterson’s aunt, Julie Long, addressed reporters to speak to her nephew’s unknown killer: “You are forgiven.”

It’s possible that Long may one day confront Patterson’s killer. Or perhaps the killer will never be found or has already died. Regardless, Long purported to exercise the act of forgiveness on someone she’d never met and whose identity is unknown to her.

In My Head

I have not had anyone close to me face the challenge of forgiving an unknown perpetrator who has significantly harmed them. But the basic principle also unfolds in more ordinary circumstances. For example, when an institution like a university or a church acts unjustly and causes harm, it is not always possible to pinpoint a single individual within the organizational structure to forgive or with whom to pursue reconciliation. Instead, we’re left with a sense that “the organization” is at fault—and it’s hard to know how to forgive an organization.

In other situations, the person who caused us harm is too far removed or entirely unknowable. Consider this somewhat unfortunate incident from my own life earlier this year:

Fortunately, the only injury other than my pride was a little soreness. But the fall could easily have led to something more serious. And what then? Someone I’ve never met, and whose identity I’ll never know, would have caused real harm to me. Is forgiveness possible—or even necessary—in this situation? Or should I instead blame the blueberry?

Theological ethicist Donald Shriver has argued that “forgiveness is interdependent with repentance” and that “absent the latter, the former remains incomplete, conditional, in a posture of waiting.” Contrary to Shriver, my hunch is that it must be within our human capacity to forgive someone who is unable to repent—either because that person has died or will forever remain unknown to us. But this necessarily severs forgiveness from repentance—and, ultimately, from reconciliation. We can find healing and wholeness in our own lives by forgiving others. But we won’t always be able to restore relational wholeness with everyone who has wronged us.

Here is perhaps an even harder truth: each of us has undoubtedly harmed others in ways that will never be known to us. What do we do in these situations? We can’t just make a blanket apology to “the world.” Perhaps we will simply have to hope that others will forgive us for our wrongs never fully revealed to us.

In the World

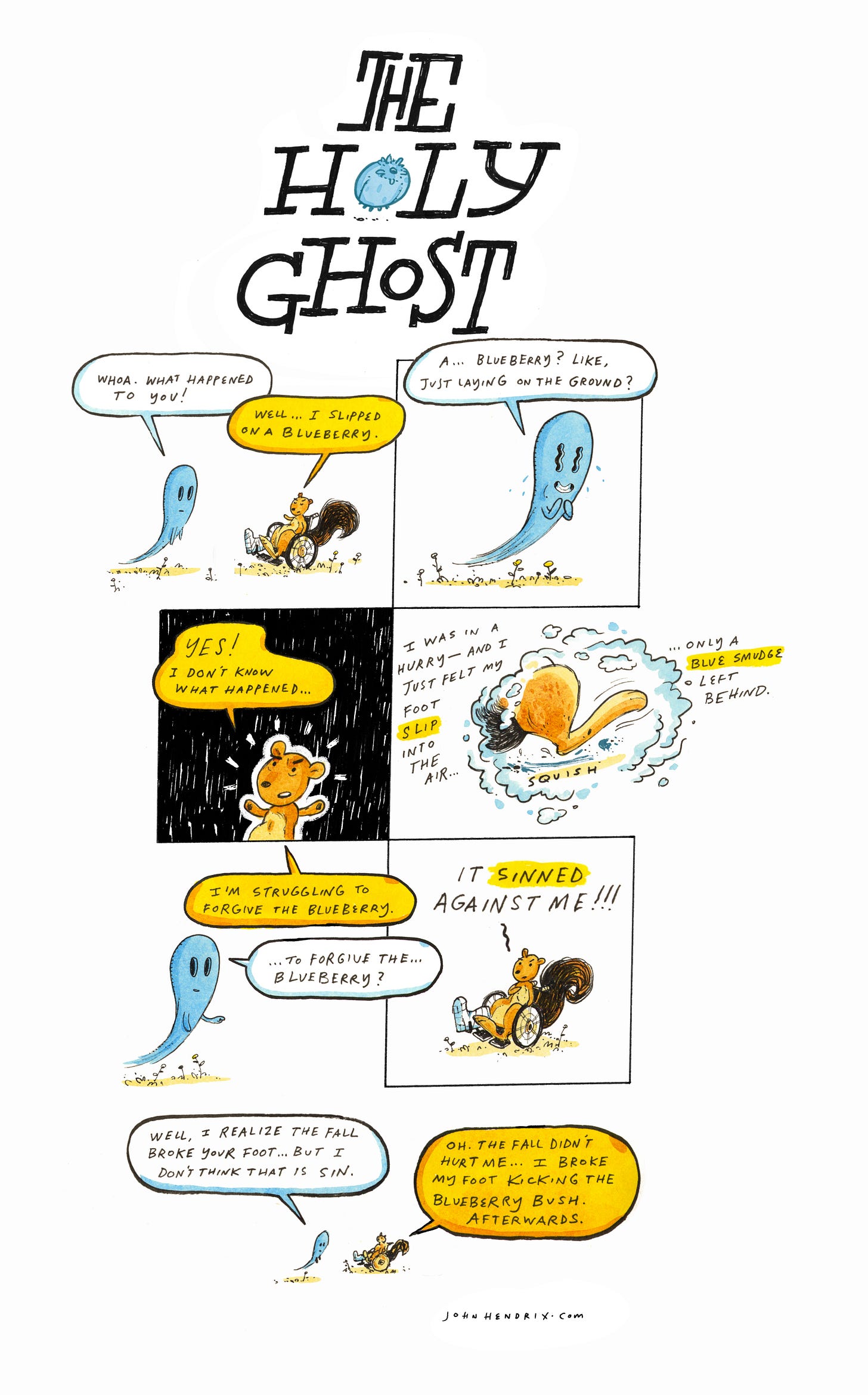

My Washington University colleague John Hendrix is a graphic novelist and the author of a number of books including The Holy Ghost: A Spirit Comic. John’s publisher describes The Holy Ghost as “a series of conversations between a squirrel, a badger, and a friendly blue ghost who may or may not be one third of the Holy Trinity.”

I saw John shortly after my unfortunate encounter with the blueberry, when we gathered with a small group of friends to discuss Keller’s book on forgiveness. During our conversation, I raised the difficulty of forgiving people we’ve never met, or whose identity is obscured by institutions, or whose actions—like dropping a blueberry—are too causally removed from the harms we experience.

John began sketching as we talked, and a few weeks later had his next installment of The Holy Ghost:

Of course, the topic of forgiveness is far weightier and costlier than wounded pride. But there may still be something to learn about the nature of forgiveness from a humorous illustrator, a hapless law professor, and a blueberry.

You can buy John’s collection of Holy Ghost comics here, though you’ll have to wait for Volume II to get the blueberry comic:

No. Amnesty.

Accountability and consequences for those human rights criminals who tried to destroy our lives. Because without those, they will absolutely do it again.

There will be no forgiveness for the psychopaths that tried to steal our livelihoods, take our freedom, and rob our children of their education and future. Keep your dark age superstitious mumbo jumbo to yourself. I want these people to be held to account , as it’s obvious by now none of them have the slightest intention of apologizing or introspecting. So it’s time for Nuremberg 2.0.