Meet Maverick, the new Inazu family dog.

This news will come as a surprise to some friends and readers of Some Assembly Required. I am, to put it mildly, not a “dog person.” To the contrary, I am terribly allergic to dogs. And the decades of watering eyes and instant congestion every time I’ve encountered a dog in someone’s house, on an airplane, or in a coffee shop has not endeared me to dogs. But I will admit that the past few days of having Maverick in our house have rapidly reversed many of my existing priors. And I think there is a lesson here about the connection between empathy, exposure, and experience.

A quick but important caveat: dogs are not people. The analogy between my newfound empathy for dogs and the challenge to empathize with people—the topic of this post and the focus of my work—is quite imperfect. But I think it’s still a helpful bridge to highlight the value of exposure and experience to increasing empathy.

Plus, how could I not show you a picture of Maverick?

In the News

The importance of exposure and experience to increasing empathy can be seen in the work of Braver Angels, an organization that I highlighted in an earlier post. Braver Angels seeks to “bring Americans together to bridge the partisan divide and strengthen our democratic republic.” The group convenes political partisans at the grassroots level through workshops, debates, and campus engagement, “not to find centrist compromise, but to find one another as citizens.”

Last month, PBS News Hour profiled some of Braver Angels’ work among Ohio voters, with participants noting their desire to understand and learn from people across the political aisle. As the title of an earlier article on Braver Angels noted, the organization believes “healing a divided nation begins face to face.”

Mere exposure is not always enough, especially when it is online. In a 2021 study of online engagement published by the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, researchers found that “simply exposing participants to ‘outgroup’ [news] feeds enhances engagement, but not an understanding of why others hold their political views.” But the study noted that when exposure to opposing views was “framed (a priori) in terms of a familiar experience like disagreeing with a friend,” participants increased their understanding of those views.

The possibility of charitably contextualizing opposing views is extremely important to scaling the kind of work Braver Angels is doing into more toxic online spaces. As a forthcoming paper by political scientist Lisa Argyle and her colleagues suggests, this scaling might be aided by artificial intelligence that helps mediate more charitable online engagements across difference. Argyle’s research study assigned an AI chat assistant to online conversations between proponents and opponents of gun regulation. The chat assistant recommended “real-time, context-aware, and evidence-based ways to rephrase messages.” Argyle and her colleagues report that artificial intelligence interventions “improve reported conversation quality, reduce political divisiveness, and improve the tone, without systematically changing the content of the conversation or moving people’s policy attitudes.” In other words, artificial intelligence that helps people situate opposing views more charitably can increase understanding of those views.

In My Head

As noted above, mere exposure and experience do not always lead to empathy. Some people harden stereotypes or distrust of certain kinds of people after limited experiences with a few. In other words, it is a mistake to think that simply exposing people to new ideas, different people, and unfamiliar experiences will increase empathy.

There is also a common tendency to generalize from limited individual experiences. If you have exposure to or experience with a small number of people from a different political, religious, racial, or cultural background than your own, you have an extremely limited window into a different perspective. Like my newfound empathy for Maverick, your empathy might be limited to your firsthand interactions with particular people. And just as Maverick does not represent all dogs, or even all Havanese, your few friends are not representatives for whatever demographic or people group you place them in.

Still, even though it is a mistake to think that knowing one person with a particular trait or characteristic represents all or most similarly situated people, knowing even one person can powerfully counteract stereotypes and generalizations. Take the matter of religion. When I hear someone talk about “the Muslims,” “the Catholics,” or “the atheists,” I find it impossible to process the claims being made without thinking about the people from within these categories whom I have come to know as friends.

Nor do we need to see empathy as an all-or-nothing achievement. I am still not a dog person, even though I now really like one dog. But I am sure the dog lovers in my life appreciate this small step in their direction. We can all take similar steps toward empathy across difference in our relationships with other people. Sometimes that means starting with exposure and experience.

In the World

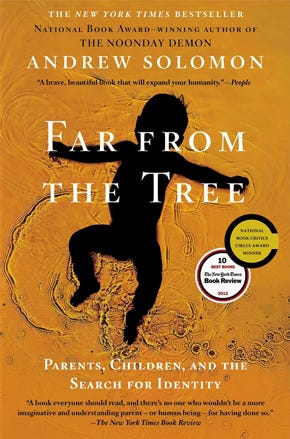

Andrew Solomon’s Far From the Tree: Parents, Children and the Search for Identity received rave reviews and numerous awards when it was first published in 2013. Solomon profiles parents whose children ended up different from them in significant ways: with deafness, dwarfism, Down syndrome, autism, schizophrenia, and multiple severe disabilities, as well as parents whose children are prodigies, who are conceived in rape, who become criminals, and who are transgender. In working on the book, he generated forty thousand pages of interview transcripts with more than three hundred families.

In each chapter, Solomon explores how parents navigate the tensions between unfamiliarity and sometimes alienation, on the one hand, and love and embrace, on the other.

It’s been a few years since I read this book, but I remember being quite moved by Solomon’s writing and the ways in which he connects empathy with exposure and experience. I part ways with aspects of Solomon’s normative vision. But appreciation for good books—like empathy for other people, or even dogs—does not have to be unmitigated in order to be meaningful.

One More Thing

I am generally cautious about sharing much about my kids in public settings. But given the topical alignment—and with their permission—here is the moment we told them we were getting a dog:

Just an aside on allergies. As a child I suffered supremely from allergies, particularly allergies to animal dander. It still bothers me somewhat, but incredibly, since going vegan, I can’t remember the last time I needed an antihistamine. I think, going off all animal products has sharply reduced the level of inflammation. I recommend a look at Dr. Michael Greger’s website blogs and videos, many of which can explain, I believe, the basis of this phenomenon. Good luck with Maverick!

Thanks for another thoughtful article and two amazing pictures, John. I knew you would come to love Mav!