Why You Can't Have All the Friends You Want

Reflections on friendship and finitude from a high school reunion

This week’s post comes out of the “people” part of the tagline of Some Assembly Required (“Protests, People, and Pluralism”).

Last week, I attended my 30th high school reunion in Colorado Springs. I generally enjoy people. And these days, I spend a lot of time speaking in front of large groups of people. I am also energized being with small groups of close friends. It’s the midsize group that freezes me—making small talk in a roomful of people I don’t really know is closer to my social nightmare. That’s especially true when I should know these people, and they should know me. And that about sums up the social experience of a high school reunion. So I was somewhat surprised that despite my perpetual social awkwardness in midsize social groups, I really enjoyed my recent reunion.

In the News

Earlier this month, Aisha Sultan observed that “Facebook should have killed the high school reunion years ago.” But as Sultan noted, an in-person reunion still brings many benefits:

It lowers stress, anxiety and loneliness while lifting mood and feelings of connection and belonging. And spending time in person with those with whom we have a strong emotional connection offers an even greater boost than any digital connection.

And, she added, “We’re getting to a point in our lives when we realize how quickly it all goes by.”

Writing for CBC News a few weeks ago, Jenifer Norwell catalogued a number of reasons people choose to attend their high school reunions. Norwell quoted sociologist Vered Vinitzky-Seroussi, the author of a book on high school reunions who believes that “reunions allow people to explore questions that haunt many humans, such as who are we and what are we doing with our lives.”

But it’s not all upside. Norwell noted “there are many reasons why people might not want to attend a high school reunion.” She quoted a woman on the cusp of her 40th reunion who quipped “I look back at my old self and I think ‘I wouldn’t want to spend a couple of hours with you.’”

In My Head

The few friends I connected with in the days prior to my reunion shared my anxiety about not remembering people or not being remembered. In my case, this memory challenge was exacerbated by missing the last 29 years of Facebook. I joined only last year at the prodding of my book agent, and I have effectively delayed the inevitable deep dive into the lives of my classmates. I also think most of my classmates rejected my friend requests as spam or Russian bots. I don’t blame them: what Gen Xer joins Facebook for the first time in 2022?

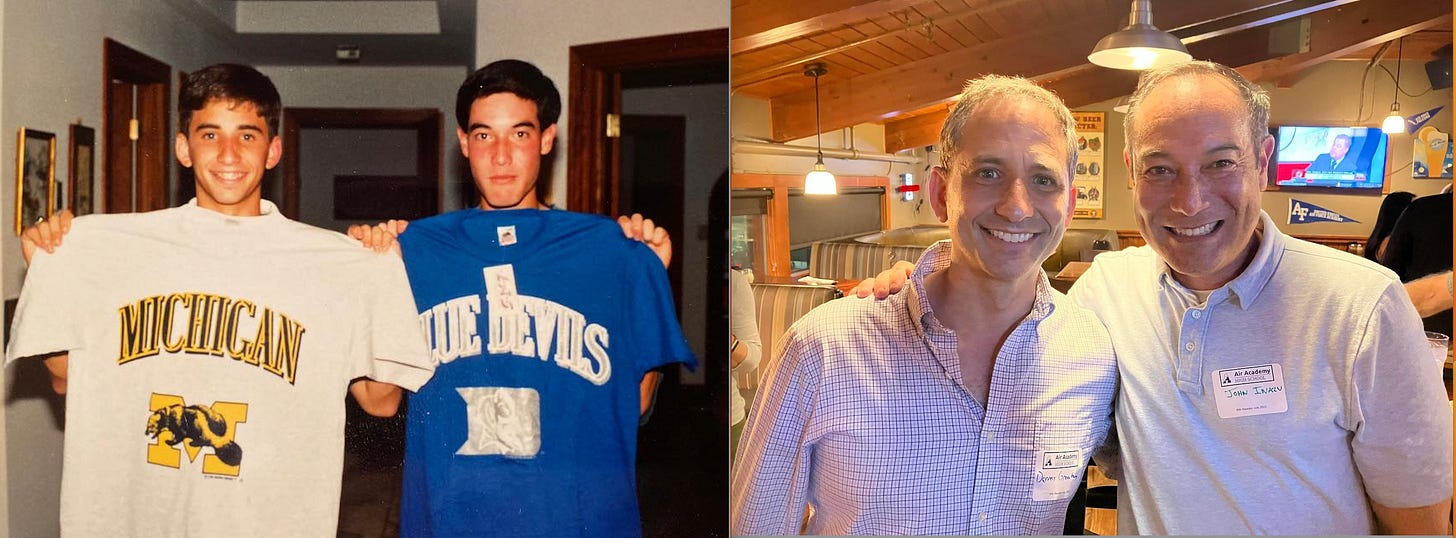

The small talk of the reunion was predictably awkward and exhausting. But that discomfort was far outweighed by longer conversations with classmates. The realization of how much of our lives has unfolded since high school left me with a great deal of gratitude for the opportunity to reconnect with old friends and acquaintances. But I’ll also admit another feeling: a sense of regret and a bit of sadness that I hadn’t kept up with most of these people and who they had become—nor them with me. Like my friend, Darren, whom I have probably only seen a couple of times since we graduated, and who showed up with old pictures on his phone and remembered to take new ones, too.

On reflection, I think this sense of regret is a normal and necessary part of being human—at least in our modern transient world. In an earlier era, and in other parts of the world today, some people lived or live their entire lives in a single small town or village. Their relational world is confined in a way that keeps them invested in those around them, with the principal disruptions of community stemming from births and deaths.

Whatever strengths and weaknesses might attach to that social reality, it is not mine. My relationships have extended across multiple communities and social networks, with varying degrees of connectedness. Other classmates have anchored more of their lives in earlier relationships. They have maintained much deeper relationships with high school friends but may not have jumped as deeply into other real and metaphorical villages. There’s not a right or a wrong path to prioritizing friendships—it is just one of the many decisions we make as human beings. We can only invest deeply in a relatively small number of people at any given time. From my limited foray into Facebook over the past year, one of its seductive draws is suggesting otherwise—making us feel more deeply connected to larger numbers of people through pictures, stories, and updates we would never have known a generation ago. This connectedness certainly has its upsides, but it also risks instilling an artificial sense of knowing and being known.

In the World

My reunion reflections called to mind Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals. Burkeman’s title refers to the average number of weeks in a human life. The book is full of useful insights and practical suggestions about how to manage time. At one point, Burkeman critiques Stephen Covey’s famous example of the struggle to fit big rocks, pebbles, and sand into a jar. Covey solves the problem by starting with the big rocks—the metaphor for our most important priorities. The pebbles and sand only fit in the jar if they come after the big rocks. But as Burkeman notes, Covey has rigged the thought experiment by assuming we have enough room in our jars for all the big rocks. And we don’t.

Our fundamental problem is not that we’ve wrongly ordered our priorities; it’s that our lives are not big enough to hold everything of importance. The solution is not prioritizing the big rocks; it’s saying “no” to some of them.

I reviewed Burkeman’s book a few years ago for The Gospel Coalition. Burkeman is not writing for Christians; in fact, he has little use for hope or faith. But as a Christian, I found much of his argument powerful and relevant to my own life. Moreover, Burkeman is right to assert:

Nobody ever really gets four thousand weeks in which to live—not only because you might end up with fewer than that, but because in reality you never even get a single week, in the sense of being able to guarantee that it will arrive, or that you’ll be in a position to use it precisely as you wish.

The limits of our time also limit the depth and number of our friendships. And that might ultimately be one of the most helpful takeaways of a high school reunion—a tinge of regret for missing out on the lives and stories of the people who were most proximate to my life and story thirty years ago, but a helpful and necessary reminder of my own finitude.

John - you've captured the essence of my own feelings with this: "The realization of how much of our lives has unfolded since high school left me with a great deal of gratitude for the opportunity to reconnect with old friends and acquaintances. But I’ll also admit another feeling: a sense of regret and a bit of sadness that I hadn’t kept up with most of these people and who they had become—nor them with me." I have such deep gratitude for being shaped, challenged, and influenced at such a critical period of life by such amazing humans. I'm motivated in an entirely new way to explore and nurture these connections. What was once 'old' has become new again. Loved seeing you, my friend. And, I'm very much looking forward to the conversations to come.

As one who has left behind that benchmark of 4,000 weeks quite a while ago (!!), now in my 60th college reunion year (!!), I can only breathe a grateful Amen! to what you've written, John. The Burkeman quote is a good secular paraphrase, of course, of James 4:13-15. "Come now, you who say 'Today or tomorrow we will go into such and such a town and spend a year there and trade and make a profit'--yet you do not know what tomorrow will bring. What is your life? For you are a mist that appears for a little time and then vanishes. Instead you ought to say, 'If the Lord wills, we will live and do this or that.'" Taking that to heart does have the potential to put many parts of one's life--in particular our relationships with people and community--into meaningful perspective.