Why 'Moderate' and 'Centrist' are Usually the Wrong Labels

Well-intentioned shortcuts mask complex political identities

One of today’s linguistic puzzles is naming people who care about politics but are not political partisans. I am one of those people. I am often called “centrist” or “moderate,” but these labels are inaccurate. I hold strong views about many issues. Many of these are not “moderate” views, and few of them represent a “centrist” midpoint of partisan positions. In fact, given the constantly shifting goalposts of what counts as “partisan,” “extreme left,” and “extreme right,” I’m not even sure how one would go about calculating what qualifies as a “centrist” view.

Here are two of my non-centrist beliefs, both of which I’ve argued are derivative from the protections of the right of assembly:

1. I believe the First Amendment protects the ability of private groups to determine their own membership (and correlatively, that government officials overregulate private groups).

2. I believe the First Amendment protects peaceful protests even when they lead to discomfort and instability (and correlatively, that government officials overregulate protests).

The first belief is generally embraced by conservatives and critiqued by progressives; the second belief is generally embraced by progressives and critiqued by conservatives. Neither of these beliefs is “moderate” or “centrist.” And combining them together doesn’t lead to moderation or centrism either.

In the News

I’m not alone in my suspicion about these kinds of labels. Last year, NPR reported on American voters who reject the political sides that emerge out of our two-party system. The article noted that there is “no magic middle” and that self-identified independents “have very little in common politically.”

These observations are not new. A 2015 Vox article by Ezra Klein noted that political opinion surveys “mistake people with diverse political opinions for people with moderate political opinions.” Klein rejected the possibility of identifying a category of moderates: “There’s no actual way to measure it, or consistent definition animating it, and it doesn’t spontaneously emerge in any of the data.”

In 2019, FiveThirtyEight ran a post titled “The Moderate Middle is a Myth.” Relying on survey results from the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group, the post cautioned against the premise that “independent” voters were simply waiting for a “centrist” candidate to emerge:

Moderate, independent and undecided voters are not the same, and none of these groups are reliably centrist. They are ideologically diverse, so there is no simple policy solution that will appeal to all of them.

The post underscored that “policy and ideology aren’t good frames of reference” for these voters because no one policy or ideology will appeal to all of them.

In My Head

I’m genuinely unsure of how to describe my politics. This post won’t offer any concrete suggestions, but I can say a few things. Feel free to share in the comments whether these observations resonate with you (and why or why not).

First, I have never been a registered member of any political party. I have voted for both Democrats and Republicans at all levels of elected office. And to the best of my recollection, I have always thought that Democrats and Republicans have both had some very good policies and some deeply harmful ones.

Second, I am confident that I am neither a political “progressive” nor a political “conservative” insofar as I find myself misaligned with almost anyone who self-identifies with either of those labels. One does not need to be politically independent to share this dual aversion—my hunch is that neither “progressive Republicans” nor “conservative Democrats” are comfortable being called simply “progressives” or “conservatives.”

I find myself in greater alignment with people who self-identify as either “moderate progressives” or “moderate conservatives.” But I still don’t feel like either of those labels accurately describes me. And I don’t think the midpoint of “moderate progressive” and “moderate conservative” is simply “moderate.”

Earlier this month, my friend David French referred to himself as an “involuntary moderate.” The adjective reflects David’s view that he is “moderate” largely because of shifts others have made. This phrasing makes “moderate” sound a lot like “reasonable” or “consistent.” But those understandings are unhelpful insofar as most people think they are the reasonable and consistent ones and others are not.

Perhaps the best I can do is describe some of my postures toward political issues. Here are three:

1) I am seldom absolutist.

On most major policy issues, I am unpersuaded by partisan absolutists in both directions. One can have deeply held views about a range of issues (like law, pregnancy, marriage, sex, and violence) without embracing absolutist policy positions stemming from those views.

I am not even absolutist in most of my strongly held policy positions. For example, when it comes to my support of associational rights, I’ve been critiqued by libertarians for not being strong enough in my views. And when it comes to protest rights, I’ve sparred with progressives who think that the First Amendment should sometimes permit property destruction.

2) I’m not certain about all of my beliefs, but I’m certain I don’t have to broadcast all of them to everyone.

I have varying degrees of knowledge and expertise. I know a lot about some issues and almost nothing about others. On those matters that I have studied deeply, I have greater confidence in the accuracy, legitimacy, and ultimate truth of my beliefs.

I could be wrong about my beliefs. But I live my life hoping they are true, as all of us must do. As theologian Kavin Rowe has observed, “the human condition is such that you have to choose how to live from among options that rule one another out.” We make that choice trusting in things unseen: “We wager our lives, one way or the other,” because “we cannot know ahead of the lives we live that the truth to which we devote ourselves is the truth worth devoting ourselves to.”

Regardless of the degree of confidence I have in my beliefs, I don’t see any reason to broadcast all of them. Part of that stems from recognizing the limits of my own knowledge and expertise. But some of it is grounded more prudentially. The world is full of injustice, bad actors, and poorly reasoned arguments. It’s not possible to confront all of these all of the time and trying to do so would be utterly life-draining. I’m amazed at the number of bright, talented, and compassionate people who waste their days policing injustices and bad arguments on Twitter.

3) I believe tone and mode of engagement matter.

The way we engage with others matters. It’s not always about winning or losing but also how we win or lose. Arguments over the most divisive issues take time to develop—they can be complex, emotional, and layered. Having the best or most logical argument is only a small part of effective persuasion. And obnoxiously shouting or sanctimoniously preaching even the best arguments inevitably renders them ineffective.

I’m aware of warnings about tone policing and arguments that critique civility. As I’ve written elsewhere, there is a place for strategic incivility that “enlists words and actions to disrupt and unsettle widely shared norms” and there is reason to view skeptically those who control the status quo and simply instruct agitators to “calm down and try being more polite.”

Still, in most cases, our mode of engagement matters. Generally speaking, restraint, charity, and inquisitiveness improve argument and dialogue. Conversely, defensiveness, rambling, yelling, and snark rarely help.

In the World

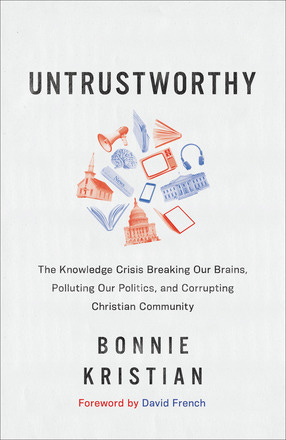

I am currently reading Bonnie Kristian’s Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community. I’ve found it helpful in thinking through how we can avoid partisan frames and recognize the limits of our own arguments and understandings.

Kristian addresses the “knowledge crisis” that stems from a flood of misinformation and entrenched echo chambers. The knowledge crisis leads to disruption and distrust in our social institutions. Kristian pays particular attention to the effects and influence of social media, cable news, and conspiracy theories in conservative Christian communities—challenges not only for those communities but also for the ways in which they engage in our broader political society.

Untrustworthy also tackles uncertainty about personal beliefs. Kristian echoes Kavin Rowe’s observations when she writes:

Obviously, I believe my beliefs are true, because if I didn’t believe that, I’d believe different beliefs. I have (what I think are) good justifications for my beliefs and would even go so far as to call them knowledge.

Still, Kristian notes how unlikely it is that every one of her beliefs is correct—that of all the people in history, she is the one who has finally figured everything out. And she asserts:

Alas, the same goes for you. The likelihood is vanishingly small that everything you believe you know is true. This is the case for all of us, all the time. To admit this . . . is not to deny the existence or knowability of truth. It isn’t to say we can never trust our senses, reasoning, or memory, or that we can’t receive knowledge through revelation or the testimony of other people. It isn’t an argument against confidence in our beliefs. It is simply to say that we are fallible and that truth, as the teacher of Ecclesiastes tells us, is often obscure.

Although Kristian is writing to Christians, many of her arguments apply more broadly. Anyone interested in learning more about the epistemic challenges facing Christians—and the political implications of those challenges for our broader society—will benefit from reading this book.

John, I resonate with your struggle to choose an identity that clearly represents my convictions which are so often nuanced in a way that a label can not describe. I also struggle that I identify more with progressives on many biblical values but more with conservatives on governing principles. For instance, debt relief is a biblical value at certain times of compassion and the Year of Jubilee. But it is not a sustainable principle for normal government functions. I guess that moderate progressive or moderate conservative are the best general approximations but discernment is needed in all political decisions that can’t be easily reflected in a label. But would a “principled moderate” identity help in at least communicating less than extreme positions while also prompting inquiry into “what principles?”

I appreciate this. Here in Canada, our politics are perhaps less polarized than yours, but there's still a tendency to want to sort everyone onto the left-right, conservative-progressive spectrum. I think Patrick Deneen's distinction, in Why Liberalism Failed, between left-liberals and right-liberals is a helpful one. He argues that the left and the right are two sides of the same ideological political project, mainly differing on whether they put the accent on unlimited individual expression or unlimited use of the natural world and its resources (but both agreeing more than they appear to disagree).

As a Christian, I've always found the conservative-progressive dichotomy to be unhelpful. Try as I might, I just can't see how Jesus could properly qualify as left or right. But since I've began working with an organization that partners with Indigenous communities here in Canada, I've found it increasingly difficult to locate myself on this political spectrum at all. For the most part, neither side represents the interests of Indigenous peoples, because doing so would undermine the Canadian political project in ways that would quickly lose politicians their jobs.

I think which communities and people we make investments in (and the shape of those investments) is more important than where we are located on the political spectrum. What I mean by this is that it's more helpful to divide the political spectrum this way: On the one end, we have people who are investing in their own social group and its social welfare in a way that gives little thought to people who experience marginalization. On the other end, we have people investing in people and communities experiencing suffering, marginalization, oppression, violence etc. The way politics is today, if you're on the former end of the spectrum, it's pretty easy to put a political label on yourself. The more you make investments on the latter end of the spectrum, the more you're forced to be a political pragmatist or political subversive, and the less labels stick.

Now I admit this is a simplistic comment-sized suggestion, but I think there's precedent for this kind of political reading (Augustine's reading of political history in the The City of God comes to mind as an analogous example).

One of the unexpected upshots of all this is that perhaps genuine healing of the toxically polarized political divide can only happen by forging genuine partnerships with people who are already experiencing the underside of the system. To me, at least, that's a good place to start.