When and Why Can the Government Restrict Our Expression?

The government should justify and explain its reasons for limiting our words and actions

One of the core functions of the First Amendment is protecting our ability to criticize government. For example, if we disagree with the actions or policies our government pursues, we should be free to voice our dissent. Today, these protections may seem obvious, but they were not always so evident—and we should not take them for granted. As Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote in his famous dissent in Abrams v. United States, we should be “eternally vigilant” against governmental limits on our expression.

In the News

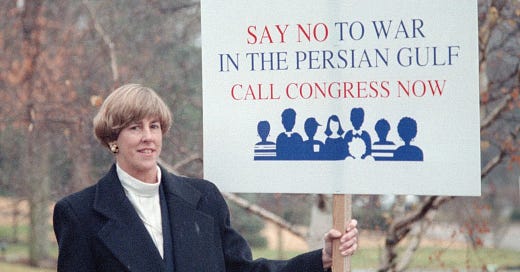

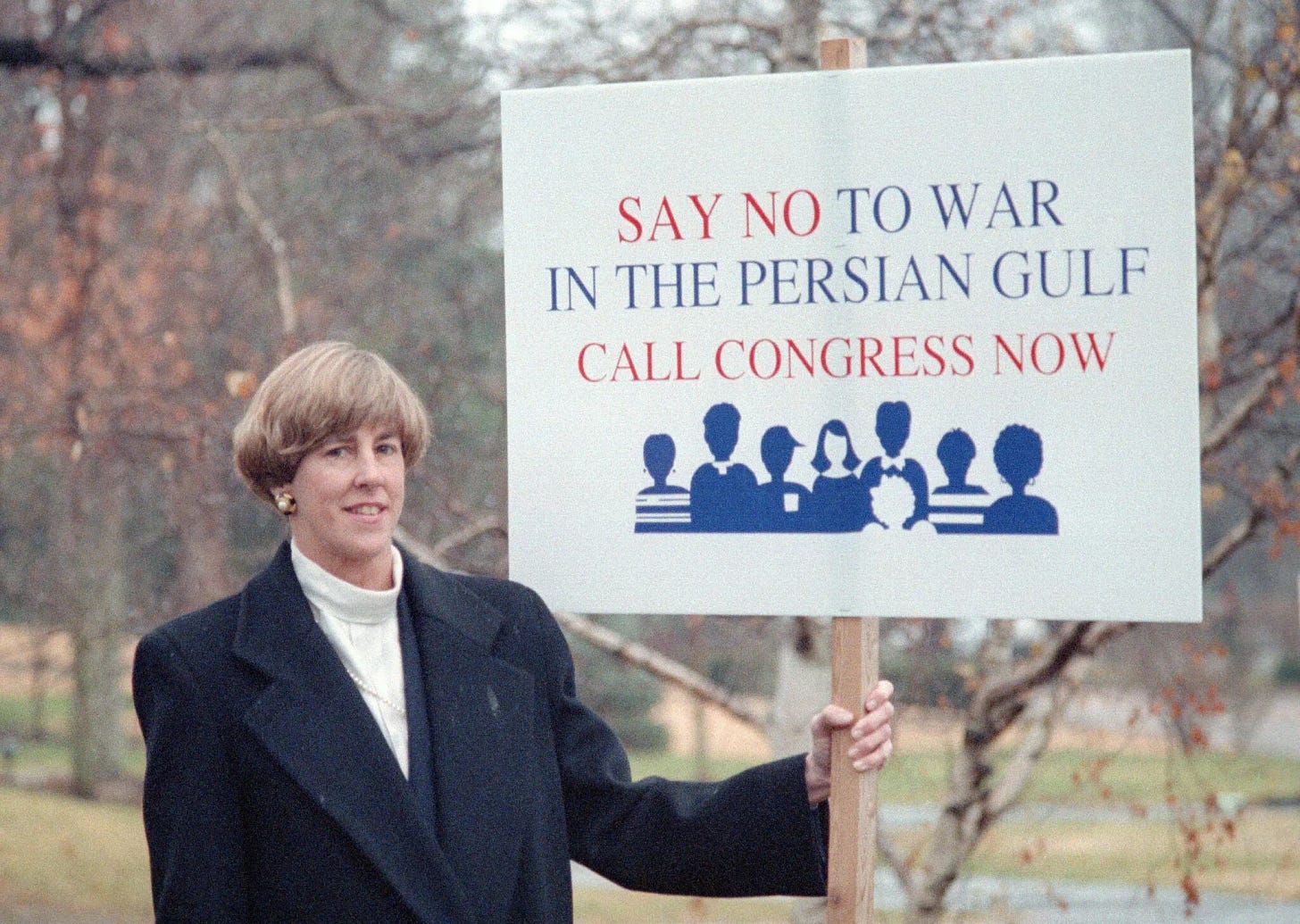

Last week, the New York Times noted the passing of Margaret Gilleo, a retired teacher who died in her St. Louis home earlier this month at the age of 84. In 1994, Gilleo prevailed in a seminal First Amendment case, City of Ladue v. Gilleo.

At the time the dispute began in 1990, Gilleo lived in Ladue, which the Times aptly describes as “a wealthy, leafy suburb west of St. Louis that had a longstanding reputation as an exclusive community, filled with residents who demanded a certain level of aesthetic beauty.”

As the United States headed toward war in the Persian Gulf, Gilleo voiced her opposition with a 3-by-2-foot sign in her yard that read: “Say no to war in the Persian Gulf. Call Congress now.” Gilleo considered herself “extremely patriotic” and said to a local paper at the time, “I love this country. I love the flag, and I would never burn it.” But she added, “I reserve the right to dissent.”

After several instances of vandalism against the sign, Gilleo complained to authorities. They informed her that her sign violated a local ordinance that restricted almost all yard signs but provided limited exceptions for real estate notices and allowed signs on some non-residential properties.

Gilleo’s case challenging the constitutionality of the local ordinance made it to the Supreme Court, where the Justices unanimously sided with her. Writing for the Court, Justice Stevens emphasized:

Residential signs are an unusually cheap and convenient form of communication. Especially for persons of modest means or limited mobility, a yard or window sign may have no practical substitute. Even for the affluent, the added costs in money or time of taking out a newspaper advertisement, handing out leaflets on the street, or standing in front of one's house with a hand-held sign may make the difference between participating and not participating in some public debate.

Justice Stevens acknowledged the city’s interest “in avoiding visual clutter” and noted that signs, unlike verbal speech, may sometimes be restricted because they “may obstruct views, distract motorists, displace alternative uses for land, and pose other problems that legitimately call for regulation.” But he added that those interests do not justify all regulations of signs, especially the near-total ban enacted by Ladue that stifled Gilleo’s political dissent.

In My Head

After learning of Gilleo’s death, I went back and reread the Supreme Court’s 1994 decision. What stood out to me on this reading is how the Court bypassed a pervasive but cumbersome doctrine in free speech law known as content neutrality to focus first on the government’s asserted interest in restricting expression.

In First Amendment cases, courts often distinguish between laws that are “content neutral” and those that are “content based.” The latter are usually more suspect. For example, a law that bans public expression during the evening would be content neutral—it does not ban expression based on its substance or message. In contrast, a law that banned Muslim prayers during the evening would single out the substance of the expression and therefore be content based.

But the distinction between content neutral and content based laws is not always as clear as courts suggest. In the example above, if a content neutral ban on evening public expression functionally restricted only Muslim prayers but little other expression, the law might still be worrisome.

One upshot of this doctrinal complexity is that courts are more likely to uphold content neutral laws. In City of Ladue v. Gilleo, the lower court had intimated that Ladue might remedy its constitutional defect by eliminating the law’s exceptions and making the restriction a total ban on outdoor signage—in other words, by making the law content neutral.

Justice Stevens emphasized this would not be enough:

If the prohibitions in Ladue's ordinance are impermissible, resting our decision on [eliminating] its exemptions would afford scant relief for respondent Gilleo. She is primarily concerned not with the scope of the exemptions available in other locations, such as commercial areas and on church property; she asserts a constitutional right to display an antiwar sign at her own home. Therefore, we first ask whether Ladue may properly prohibit Gilleo from displaying her sign, and then, only if necessary, consider the separate question whether it was improper for the City simultaneously to permit certain other signs.

This initial focus on the nature and strength of the government’s interest (“we first ask whether Ladue may properly prohibit Gilleo from displaying her sign”) seems exactly right to me. But the Court often neglects it by beginning with an inquiry into content neutrality. Justice O’Connor, in fact, emphasized the irregularity of Justice Stevens’s sequencing in her concurrence: “The normal inquiry that our doctrine dictates is, first, to determine whether a regulation is content based or content neutral, and then, based on the answer to that question, to apply the proper level of scrutiny.”

In the World

Today I’m flagging an academic article of mine that will be published later this year in the Brooklyn Law Review. I began writing this article when I noticed the very distinction that Justice O’Connor highlights in her concurrence in City of Ladue v. Gilleo: the order in which courts analyze the nature and strength of the government’s purported interest in regulating expressive speech or activity in First Amendment cases.

Cases like City of Ladue v. Gilleo suggest why this matters. Current First Amendment analysis too often minimizes or ignores a meaningful assessment of the government’s purported interest in limiting expressive liberties. This challenge is compounded by confusion and uncertainty introduced by doctrines like content neutrality. The result has been a great deal of confusion and head-scratching, including by lower courts attempting to apply Supreme Court precedent.

My article, “First Amendment Scrutiny: Realigning First Amendment Doctrine Around Government Interests,” proposes a uniform strict scrutiny test across all five individual rights in the First Amendment (speech, press, petition, assembly, and the free exercise of religion). My test would require that a government restriction on First Amendment expression or action advance a compelling interest through narrowly tailored means and not excessively burden the expression or action relative to the interest advanced. This test resembles an existing First Amendment assessment known as strict scrutiny. But it adds clarity and transparency to the balancing inherent in First Amendment cases, and it requires the government to justify its asserted interest in restricting expression. A meaningful strict scrutiny test would not mean the government always loses. But it would mean the government always justifies its restrictions.

I am currently finishing my last round of substantive edits, and I would welcome any feedback you might have in the next few days (my revisions are due to the fine editors at the Brooklyn Law Review on July 10, so send comments soon!).

One More Thing

I try to write weekly about something interesting to me that I hope will be useful to readers. I occasionally weigh in on breaking news directly relevant to my expertise, but most of my posts will not be about the biggest and most recent headlines. For that reason, as I note in the overview of Some Assembly Required:

You might get a newsletter about some seemingly obscure or even light-hearted topic within a few hours of a major development in the news cycle or in your life. Those kinds of unintended interactions create dissonance for all of us. My advice is to focus on what’s important in the moment, which sometimes won’t be my newsletter.

Thanks to all of you for reading!