The University as a Place for Disagreement

Remembering a core purpose of education at the beginning of a new academic year

It’s that time of the year when colleges and universities welcome students back to begin the academic year. Earlier this month, I was privileged to address Washington University School of Law’s first year class on the topic of “confident pluralism in law school.” I suggested that in light of deep and irresolvable differences, we need to learn to find common ground even when we can’t agree on the common good. This is especially important in law schools because our society relies on lawyers and law to address irresolvable differences through rules and norms instead of through violence. That, in turn, requires establishing and maintaining a robust and responsible culture of free expression.

I gave a similar talk to last year’s incoming class, which I summarized in this post. I also share the substance and experience of this talk in the opening chapter of my next book, Learning to Disagree.

In the News

I am not the only one advocating to students about the importance of engaging with diverse viewpoints and perspectives. Across campus, Washington University Chancellor Andrew Martin’s convocation address focused on the importance of free expression. As reported in The Source, Martin focused on the responsibility from all sides:

These challenges to freedom of inquiry aren’t limited to any one side of the political aisle and they are always antithetical to who we are and who we wish to be. I believe that the highest use of free speech is to search for the truth. If we’re afraid to ask questions about history, or identity, or anything else, our work no longer serves our mission, as described by our motto, ‘per veritatum vis,’ or strength through truth.

Martin also suggested that some efforts “to limit the types of questions students and professors can ask” come from people who “don’t want to contend with the implications of the potential answers.”

I was pleased to read Chancellor Martin’s commitment to free expression. As I noted in an earlier post, last month a group of college and university presidents announced a new initiative pursuing similar themes.

In my Head

The aspirations of university administrators are important to convey at the beginning of the year, but they will be much harder to put into practice over the course of the academic year. The more difficult and related challenge of schools like Washington University is their need for greater clarity around their core purpose and mission. Doing so would help explain why free speech and inquiry are so crucial to higher education.

Earlier this week, Stanford professors Debra Satz and Dan Edelstein wrote a New York Times opinion piece titled “By Abandoning Civics, Colleges Helped Create the Culture Wars.” Satz and Edelstein argue that “intolerance of ideas is not just a consequence of an increasingly polarized society” but “also results from the failure of higher education to provide students with the kind of shared intellectual framework that we call ‘civic education.’”

By defining the university’s purpose and mission as the pursuit of knowledge, the cultivation of civic skills, and the opportunity to explore differences—claiming the university as a place for disagreement—schools could establish coherent boundaries around free inquiry and build a culture that enforces those boundaries and protects all expression that unfolds within them.

As Satz and Edelstein note:

In the absence of civic education, it is not surprising that universities are at the epicenter of debates over free speech and its proper exercise. Free speech is hard work. The basic assumptions and attitudes necessary for cultivating free speech do not come to us naturally. Listening to people with whom you disagree can be unpleasant. But universities have a moral and civic duty to teach students how to consider and weigh contrary viewpoints, and how to accept differences of opinion as a healthy feature of a diverse society. Disagreement is in the nature of democracies.

Foregrounding these goals will require all of us—teachers, administrators, and students—to create an environment and a culture that focuses on the core purposes of the university as a place for disagreement. That is no small achievement. As Chad Wellmon has observed, such a culture must reflect “robust epistemic virtues—an openness to debate, a commitment to critical inquiry, attention to detail, a respect for argument—embedded in historical practices particular to the university.”

In the World

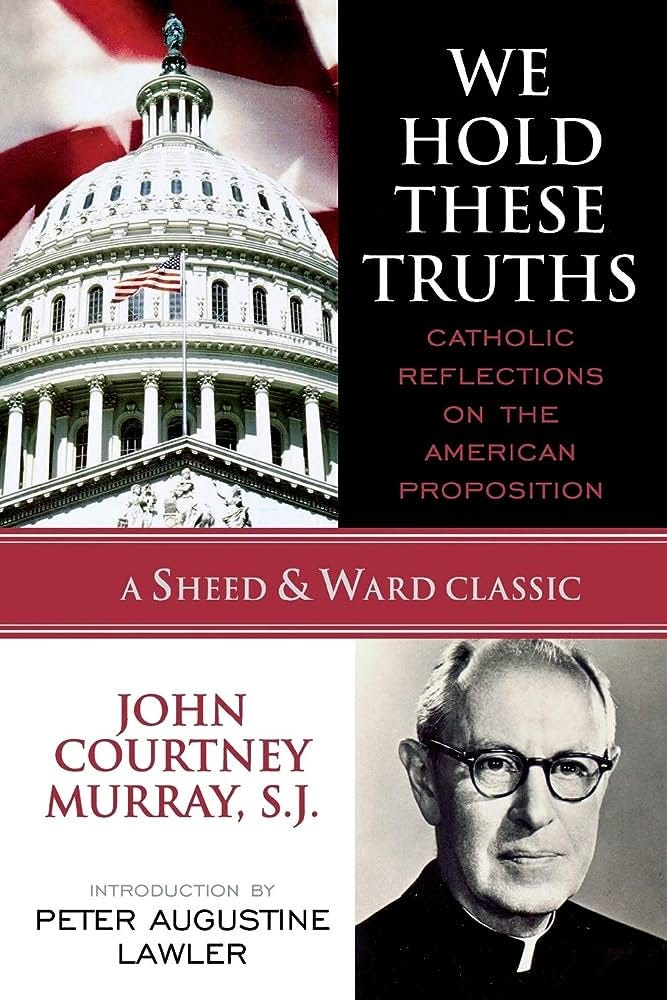

I am tempted to mention a certain forthcoming book now available for preorder, but I am confident that I will be doing that enough over the next few months. Instead, I’ll highlight John Courtney Murray’s classic text, We Hold These Truths: Catholic Reflections on the American Proposition. Murray’s book is still available for purchase but is also freely available online through Georgetown University’s library.

Murray’s fifth chapter focuses on pluralism and the university. He begins by defining the university as “that social institution whose function it is to bring the resources of reason and intelligence to bear, through all the disciplines of learning and teaching, on the problems of truth and understanding that confront society because they confront the mind of man himself.” He pays particular attention to the role of religious students who bring their various faith commitments to the life of the university and observes:

There can be no question of any bogus irenicism or of the submergence of religious differences in a vague haze of "fellowship." It is not, and cannot be, the function of the university to reduce modern pluralism to unity. However, it might be that the university could make some contribution to a quite different task—namely, the reduction of modern pluralism to intelligibility.

Or, as the title of Murray’s fifth chapter suggests, the university should be a place where creeds are intelligibly at war with one another. As I have argued elsewhere, Murray’s condition of intelligibility creates the possibility of genuine dialogue across difference. Disagreement without any constraints opens the door to manipulation and even violence. Similarly, creedal war with no intelligibility renders communication impossible. In the university, most disagreements should be modestly constrained and most creedal wars somewhat intelligible.

This is the kind of framework that allows the participants in a university to pursue free inquiry not only in its opening ceremonies but throughout the course of the year. As Murray reminds us, the questions explored within this framework redound not only to the university but to the larger society as well:

How much pluralism and what kinds of pluralism can a pluralist society stand? And conversely, how much unity and what kind of unity does a pluralist society need in order to be a society at all, effectively organized for responsible action in history, and yet a “free” society?

If we cannot tackle these questions within the university—a place for free inquiry and robust disagreement—I am not sure where else we can look to address them.

I didn't realize until reading the bit about how you would not discuss a certain forthcoming book how the ability to link to things offers a wonderful technology for engaging in praeteritio.

Yes, John, where else if not in the university?