Questioning the Sincerity of Religious Belief is a Bad Idea

Legal constraints on the free exercise of religion should not hinge on assessments of sincerity

A few years ago, I wrote in Newsweek about my experience showing the 2006 documentary Jesus Camp in one of my undergraduate seminars. Jesus Camp explores the ways in which certain Christian fundamentalists train and sometimes indoctrinate their children into their religious commitments.

Reflecting on my seminar, I recalled:

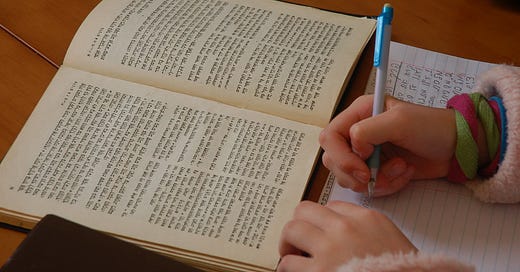

One of my favorite moments as a teacher came when a Jewish student in the class shared her reaction to the film: “I kept thinking as I was watching what someone would have said if they had visited the Jewish summer camp that I attended growing up. We had prayers and rituals that felt normal to me but would have looked bizarre from the outside.”

My student’s astute recognition enabled her to empathize with the unfamiliar, in part because she recognized how strange her own practices would look to others.

I used that illustration in 2020 to weigh in on the controversy surrounding the faith practices of Justice Amy Coney Barrett and suggested:

One way to protect against assuming the worst of our fellow citizens is to work toward charitable descriptions of one another's practices. We might consider that for Christians, the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper is not simply an opportunity to “drink my little wine . . . and have my little cracker,” [as Donald Trump once characterized it] but a profound spiritual and bodily remembrance that “Christ has died, Christ has risen, Christ will come again.” We could remember that Muslim prayers are not empty rituals but vital reminders of one's daily connection to God. We could recognize that Jewish holy days are not excuses to take time off from work or school but opportunities to connect with expressions of faith that build on centuries of practice.

Seeking empathy toward unfamiliar religious beliefs and practices is one of the best ways we can honor the religious diversity in our country.

In the News

Recent months have seen claims of religious freedom in a number of hot-button issues. Two in particular stand out. First came religious objections to vaccine requirements from conservative Christians. Then came religious objections to abortion restrictions from progressive Jews, now particularly salient in light of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. The logic of both arguments is similar: the claimant argues that her religious convictions prevent her from following a duly enacted state law (a vaccine requirement or an abortion restriction). Both claims have been met with skepticism.

When it comes to vaccine challenges, the New York Times observes:

For many [vaccine] skeptics, resistance tends to be based not on formal teachings from an established faith leader, but an ad hoc blend of online conspiracies and misinformation, conservative media and conversations with like-minded friends and family members.

Law professor Josh Blackman makes a similar critique of Reform Jews who claim that Jewish law requires abortion in certain circumstances:

Judaism is not a centralized religion. There is no Jewish equivalent of a Pope. We often speak of "Orthodox," "Conservative," and "Reform" Jews, but even within these categories, there is no official or standardized set of teachings. Every Congregation, indeed, every Rabbi, may follow the teachings in different fashions. Moreover, every Jew can look to faith in his own fashion. And there is no obligation to be consistent. A Jew could hold one opinion in the morning, and then change his mind over lunch, and go back to the original position after dinner. The old saw, Two Jews, Three Opinions, is apt.

Blackman concludes “The Free Exercise Clause applies to all people, but the question of whether a law substantially burdens the free exercise of religion turns on how a person practices her faith.”

In my Head

Free exercise law is in a bit of flux, including the level of scrutiny courts should apply to government restrictions on religious practice. In both the vaccine and the abortion cases, one could argue that protecting human life is a compelling government interest that justifies restricting the practice. For present purposes, however, I’m less interested in the strength of the government’s interest than in the predicate question of whether the underlying religious claim is sincere.

Based on existing law, Professor Blackman is clearly wrong in his assertion that substantial burden “turns on how a person practices her faith.” Free exercise law has long deferred to idiosyncratic and even post-hoc faith claims, and judges typically assume the sincerity of religious claims, including claims related to substantial burden.

The vaccine and abortion cases raise a related but distinct question of whether these kinds of claims are being used principally for political rather than legal reasons. In other words, perhaps the litigants are enlisting religious beliefs in service of clever arguments against laws they don’t like. Even if this is the case, there’s no logical reason that the claims can’t be both sincere and strategic. This happens frequently in cause-oriented lawyering.

Challenges to the sincerity of religious claims are complicated because they simultaneously impugn legal and personal integrity, suggesting: (1) you shouldn’t receive religious freedom protection; and (2) your basis for asking for protection is a sham. For this reason alone, I’m inclined to support the current approach of generally accepting the sincerity of religious claimants. If there really is a compelling government interest in restricting religious freedom, then courts should explain and defend that interest.

In the World

Not everyone thinks deferring to religious sincerity is a good thing. Writing in the Atlantic, Linda Greenhouse asserts that sincerity is “an issue that both liberal and conservative judges have too willingly overlooked for too long.”

Law professor Nathan Chapman makes a similar critique of the Court’s treatment of sincerity, noting “the ongoing confusion for many jurists and scholars about the constitutional concerns surrounding an inquiry into a claimant’s religious sincerity.” He argues that “courts can and should adjudicate an accommodation claimant’s religious sincerity,” especially because “insincere claims impose costs on the government, third parties, and religious liberty itself.”

I’m skeptical of Chapman’s prescription, for some of the reasons I noted above. But if he’s right that we can adjudicate sincerity, we should be able to do so regardless of the ideological footing of the claimant. On this particular issue, the sincerity of the vaccine objectors and the abortion restriction objectors stands or falls on the same logic. Read the article for yourself and see what you think.

A personal application

The next time you encounter a religious objection you don’t like or find disingenuous, why not ask the person making it why they think it’s important?

Good observations, John. You remind me of the dilemma draft boards would face (back in the day) if/when a member of a mainline denomination would claim Conscientious Objector status. As I recall, the draft boards had the right to question such individuals to assess genuineness of their objection to taking up arms in military service to the country. These contemporary flash points raise similar issues, and the current political climate tends to amplify the intensity of feelings on each "side," to increase one's skepticism toward the claims of those with whom we disagree. "You can't possibly be serious!" Tricky stuff.

Based on this, is there a anything to define what is a “religious claim” or even a “religion”? It seems to define these terms so broadly they have no meaning.