Author’s note: Pardon the detour from my typical format for this special post.

Several years ago, when my kids were little, I remember flying to Colorado with our two oldest, then about 4 and 2. Just the three of us. Between our carry-ons, my briefcase, the diaper bag, and the stroller, I was short a few hands as we made our way through the TSA checkpoint. I had no choice but to enlist the help of strangers, a few of whom glared annoyingly, but most of whom readily assisted.

I thought of that travel experience a few different times this past Sunday during my four-hour drive from the Los Angeles area to Manzanar Internment Camp. I was “in the area” for a conference, but it turns out nothing is really that close to Manzanar:

Eighty years ago, my grandparents traversed this same route. While I went by an air-conditioned rental car and listened to eighties music on the way, they were forced onto a train, and then a bus, before arriving at the gates of Manzanar. I’m guessing their journey took 8-10 hours.

At the time, my grandmother was 29 and my grandfather was 35. They had with them my three uncles, then ages 6 years, 2 years, and 4 months. They also had my grandfather’s parents, one of whom was in a wheelchair. They were allowed one suitcase per person. I wonder who helped them through the security checkpoints they encountered.

When I was in middle school, I had the good sense to interview my grandmother about her experience. She began by talking about their journey to Manzanar:

We were planning to build a house in Santa Monica, but we had to take out all of our savings. On Tai's birthday, May 17, we had to go into camp. Most of the other Japanese families had already gone to temporary holding areas like the racetrack. We were excused from going there because we had an invalid mother. We were only allowed to take one suitcase apiece, so we couldn't even bring blankets. We boarded a train and headed for Manzanar. When we got there, that was the saddest time. There were about twelve trains that had come in from Los Angeles and everyone was rushing to the hospital. We couldn't even get baby formula. My mother-in-law was in a wheelchair, and we couldn't even push it because the place was so sandy. When we got to our barracks, we were exhausted. I opened the door, and all that was there were a couple of cots and some blankets. I just stood there and cried.

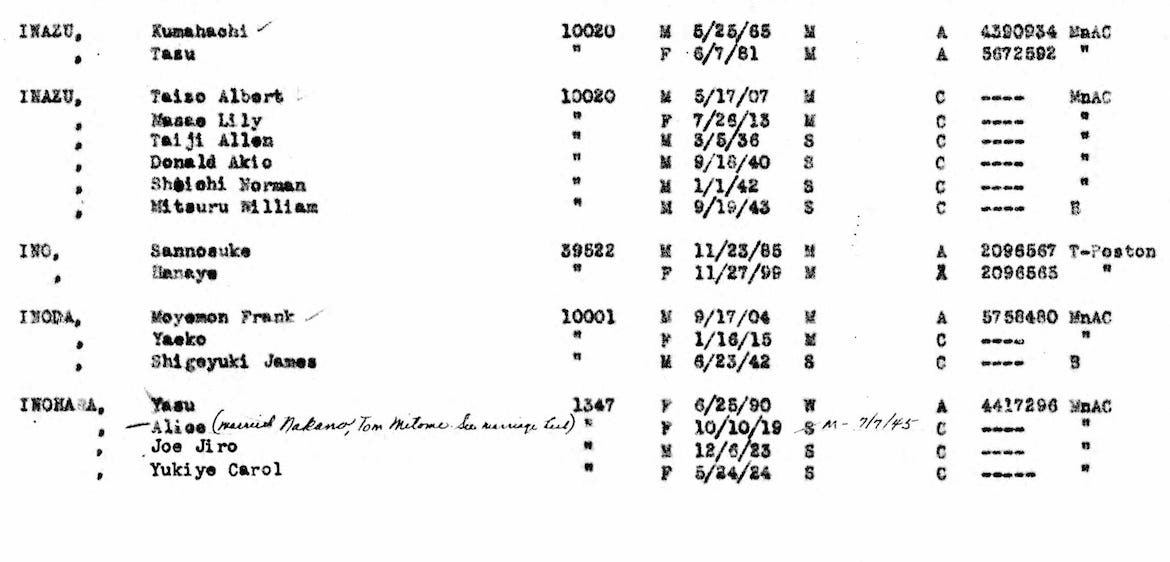

Their family of seven would soon become eight with the arrival of my father just over a year later. The federal government designated them as Family 10020:

The image above is taken from the final government registry compiled at the end of World War II. The “C”s show that my grandparents, uncles, and dad were all American citizens. The “B” at the end of the entry for my dad, William Mitsuru Inazu, indicates he was born at the camp—one of 541 Manzanar babies.

During the war, Manzanar incarcerated over 11,000 of the 120,000 interned Japanese Americans; at its peak, it housed over 10,000 prisoners. By comparison, the largest federal prison today is the minimum-security facility at Fort Dix—it houses just over 3,000 prisoners.

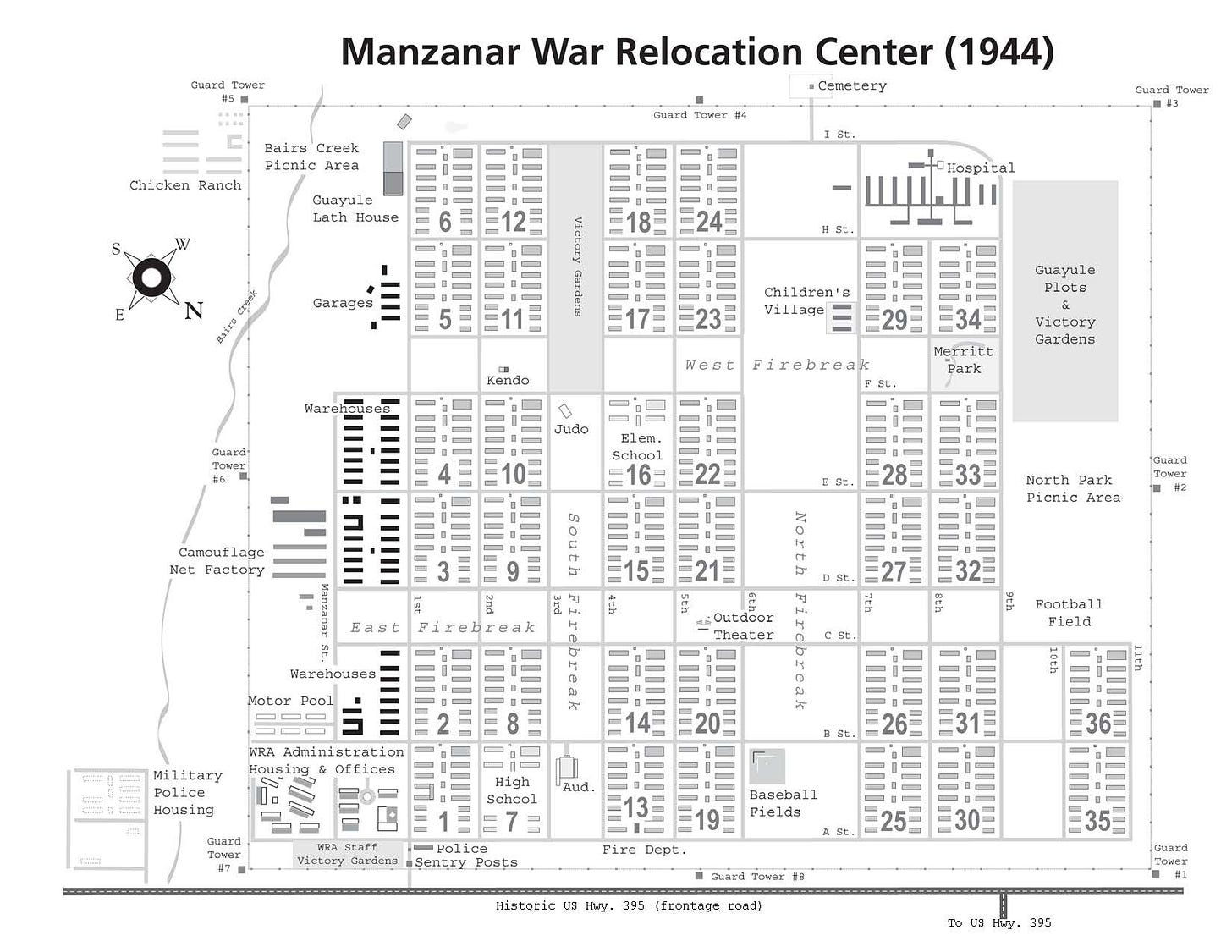

At Manzanar, internees were housed in one of 30 blocks. Upon their arrival, the Inazus were assigned to 25-12-1: Block 25, Barracks 12, Apartment 1. You can see it near the bottom right corner of this map of Manzanar, to the right of the baseball fields:

Each “apartment” was 20 x 25 feet, which meant that when my dad was born, the eight Inazus shared 500 square feet of living space. That works out to just over 60 square feet per person. The American Correctional Association currently calls for a minimum of 70 square feet per incarcerated person.

There were no bathrooms or showers in the apartment; for those, everyone had to use common latrines. For the 300 captives in each block, the military allotted eight toilets and two urinals for men, and ten toilets for women. The toilets sat side-by-side with no privacy, and the shower heads were in one common room. I remember my grandmother speaking often of the humiliation of using the latrine.

Thanks to the kindness of the National Park Service ranger on duty, I was able to locate the exact location of the Inazu apartment:

The concrete slab in the distance is the foundation of the women’s latrine for Block 25.

I was surprised by the amount of glass and porcelain shards strewn around the barracks in each block. On reflection, it made sense: when the government closed Manzanar, they hastily deconstructed the temporary facilities, and any remaining personal items were likely an afterthought. Because 16 U.S.C. § 470ee makes it a federal crime to remove items from public lands, I may or may not have taken a porcelain shard from the spot of land on which Block 25, Barracks 12, Apartment 1 once stood. If I am ever prosecuted, I will ask for equitable consideration.

The guard towers at Manzanar were spaced along the barbed wire that encompassed the camp. They were manned by soldiers with machine guns. The National Park Service has reconstructed Guard Tower 8, which overlooked the Inazus:

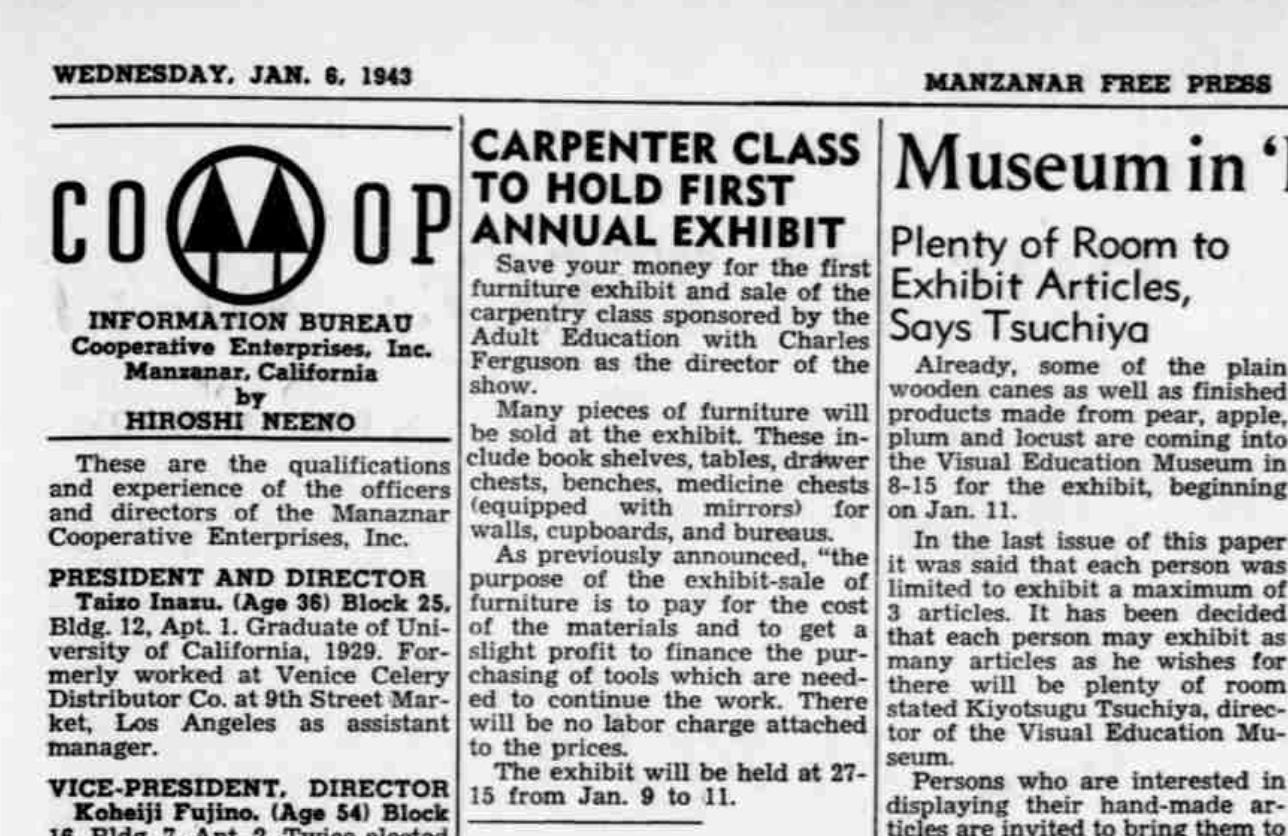

The prisoners at Manzanar established civic institutions within the camp, including a bi-weekly publication, the Manzanar Free Press, which ran from April 1942 until October 1945. The issues of the Manzanar Free Press are now available online through the Library of Congress. They helped me connect some of the stories I’d heard from my grandmother to the wider Manzanar narrative.

My Grandpa Tai assumed the leadership of the Manzanar Cooperative Enterprises shortly after it was incorporated. Here is the announcement in the January 6, 1943, edition of the Manzanar Free Press:

I was struck that the announcement highlighted my grandpa’s credentials—he had an engineering degree from Berkeley and held a managerial position at a large celery distributor in Los Angeles before the war.

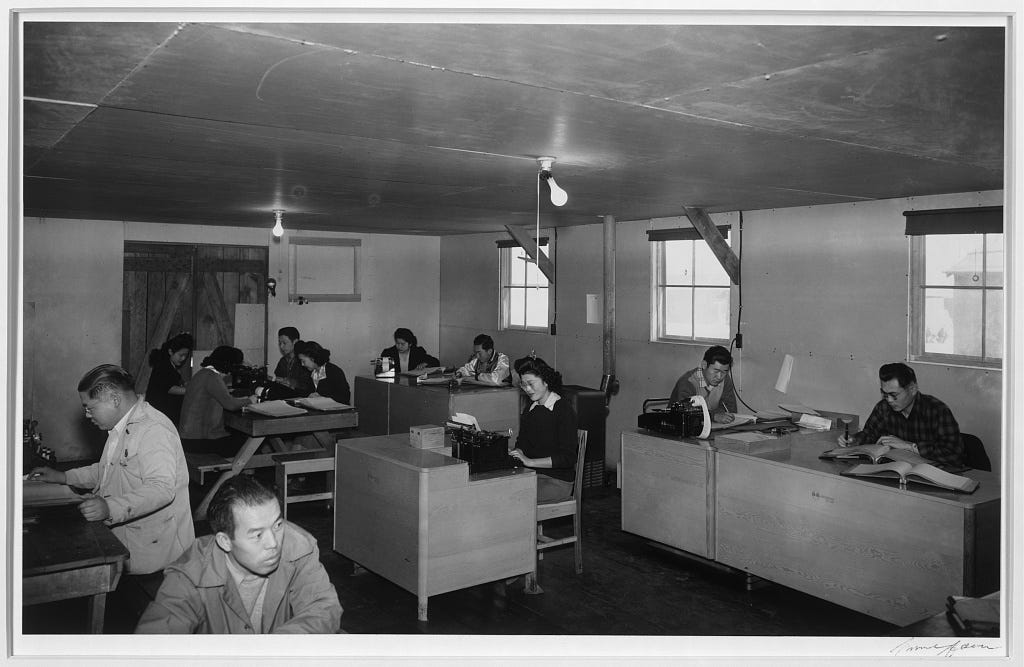

The Manzanar co-op employed 239 internees and operated retail stores throughout the camp. A 2020 article by David Thompson reports that almost every adult internee at Manzanar joined, making it the second-largest co-op in the country. Here is a photograph of the co-op office taken by Ansel Adams:

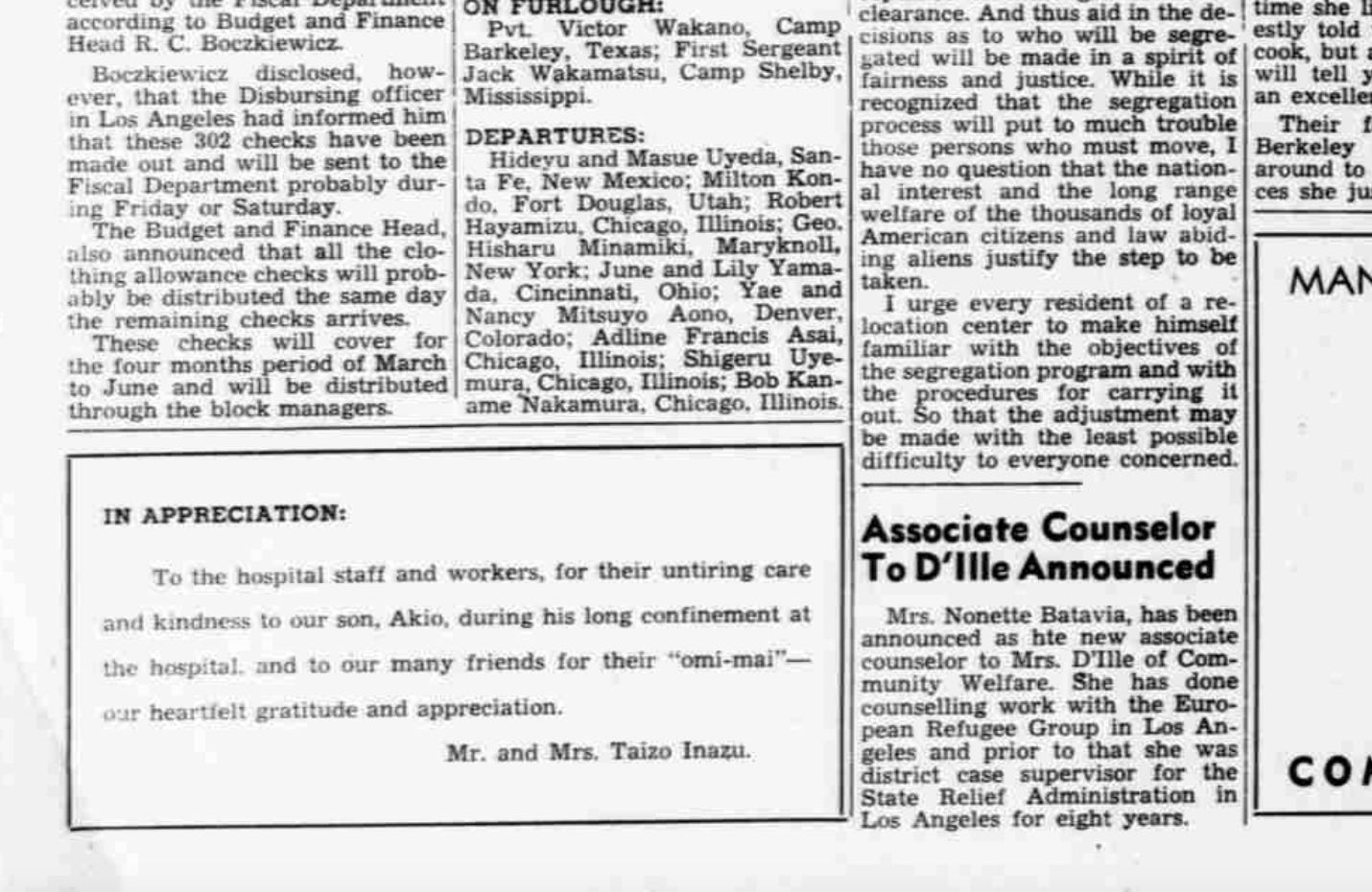

The second insight into my family’s experience came from the July 31, 1943, edition of the Manzanar Free Press. Several months prior to its publication, my uncle Donald had been badly injured. My grandmother described what happened when I interviewed her:

One day Donald got in a terrible accident. They were using a big oil truck to water down the road because it was so sandy, and when the truck came around, the older boys rushed to hop on the back for a ride. Donald watched the boys and thought it looked like fun, so he tried to hop on. The truck pinched his back and separated his pelvis an inch and a half. Someone had to run almost two miles up to the hospital to get the jeep because there were no phones. I was seven months pregnant, but I had to carry Donald halfway to the hospital until the jeep came.

Donald apparently spent quite a bit of time in the Manzanar hospital but managed a complete recovery. My grandparents took out an ad in the Manzanar Free Press:

In February 1944, my family was transferred to a more secure facility at Tule Lake after my grandfather raised questions about their incarceration as American citizens. When the war ended, they relocated to Palmyra, New Jersey, and my grandfather took a job with Westinghouse in Philadelphia. Grandpa Tai never recovered from the indignation of internment; he died in 1958 at the age of 51. My Grandma Lily raised five kids in poverty as a single mom; she died in 2013 at the age of 99.

My dad went to Rutgers on an Army ROTC scholarship. After two tours in Vietnam, he spent thirty years as an Army officer. For most of his career, he ran Army hospitals. He died of lung cancer in 2019.

Here is a picture of his birthplace, where the Manzanar hospital once stood:

What does this reflection have to do with a newsletter about Protests, People, and Pluralism? Consider this excerpt from an editorial in the October 2, 1943, Pacific Citizen, in the same issue that announced the birth of my father:

The American dream is not only one of political democracy, but also of racial democracy—where all men live together as equals. Racial or social democracy is not easily won, but will take a long time and much strategic planning by all involved. Racial brotherhood does not just depend upon the white man giving up his superiority complex, but also upon the colored man asserting his worth as an equal. We can only lead the white man to humility and the colored man to a sense of dignity by careful thought—or else there will be nothing but the exchange of places, with the Oriental and African lording it over the whites. The reward for the next few generations who participate in the effort towards social democracy will not be in victory but in having part in preventing racial conflict and the adventure of building a sound base for racial brotherhood and cultural synthesis.

The editorial’s realism disavows “victory” and focuses instead on “preventing racial conflict” and participating in “the adventure of building a sound base.” These remain worthy albeit unrealized goals of a genuine pluralism in our society. And the remnants of Manzanar stand as a stark reminder of why we can’t give up on those goals.

Thanks for reading this reflection, and thanks to Julian Lockhart, the extraordinarily kind park ranger who made my visit as rich as it was.

John, wow. The excerpts of your interview with your grandmother, the personal details and stories, the image of the government registry, the map of the internment camp, glimpses of the Manzanar Free Press and the co-op at work, plus your own photos from when you visited... all of it together made this a particularly powerful post. It underscores the reality that these things happened to real people in a specific time and place and that the effects reverberate into the present. I really appreciated the excerpt from the Pacific Citizen editorial at the end for the clarity it provides on what our common goals ought to be. While it’s hard to speak in generalities and still maintain accuracy, my sense is that the spirit of the age is one of seeking victory, whether for the aggrieved or for those who don’t wish to relinquish dominance. No matter who “wins,” in a pluralistic society, such victory can only be pyrrhic. So we have to concentrate our efforts on the things that will support peaceful coexistence and mutual thriving in shared space and time. I often think of what Dalia Eshkenazi Landau, whose family fled Europe and settled in Israel following the Holocaust, said: “Our enemy is the only partner we have.” (From The Lemon Tree by Sandy Tolan)

John, I grieve the injustice and suffering inflicted on your family. Your sharing of their story honors them and honors God. Thank you.