Can Lawyers Survive Legal Practice?

The next generation of lawyers will need to rethink the practice of law

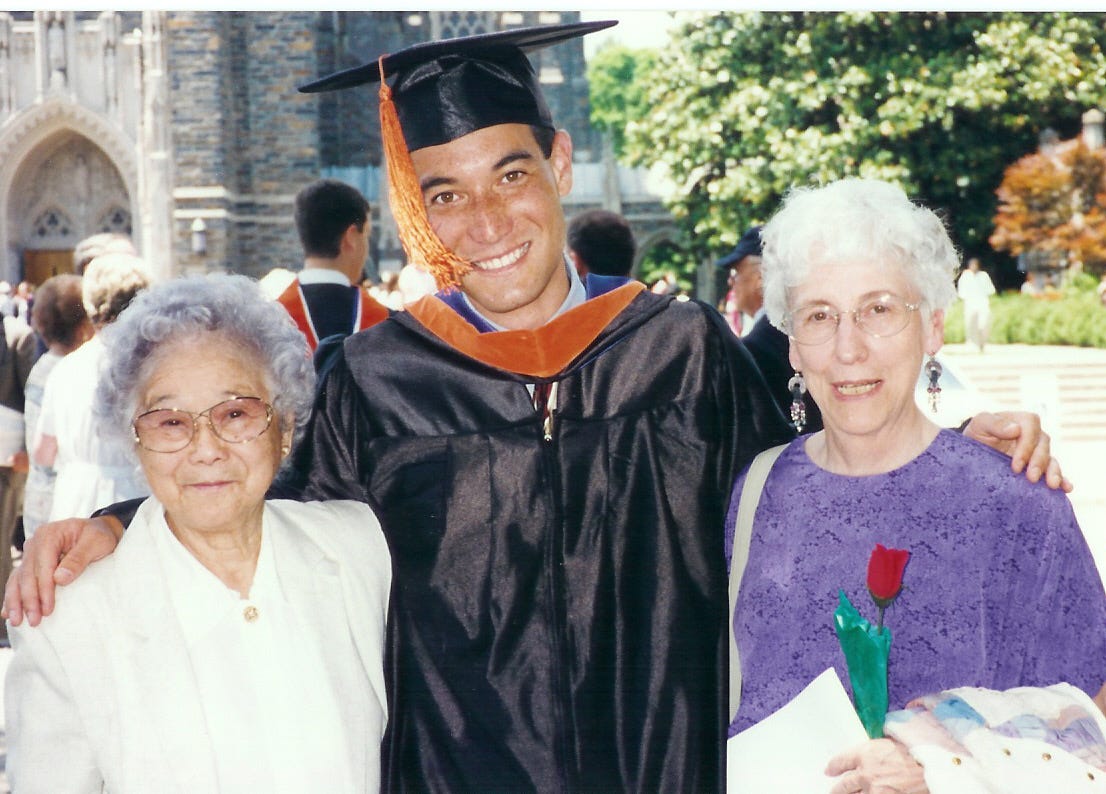

One of life’s undeserved gifts was having both of my grandmothers attend my law school graduation in Durham, North Carolina. It was a year before 9/11, when we could still meet people at the airport gates.

Grandma Arlene (pictured on the right at my college graduation, but they were both back three years later) greeted me enthusiastically as she got off the plane:

“John, congratulations, you’re a lawyer!”

And then, without missing a beat: “. . . a dirty, stinking, rotten lawyer.”

Grandma Arlene never had much of a filter. And I’m quite sure that she was simply channeling Matlock or one of her other favorite lawyer television shows. But her sentiment was not uncommon then or now. Lawyers are not usually known for their virtue or kindness. In fact, lawyers behaving badly routinely make headlines in everything from challenging election integrity to extorting their own clients. According to a 2022 Gallup Poll, fewer than 20% of Americans think lawyers have “high” or “very high” standards of honesty and ethics.

In the News

Some of the more sensational media stories contribute to the negative public perception of lawyers. But the structural problems run far deeper than the headlines. In many cases, legal practice produces and replicates systems and habits that are not good for the soul.

The evidence is hard to ignore. A 2016 study of almost 13,000 attorneys found substantial rates of problematic drinking and mental health distress, with 20% of respondents showing indications of “hazardous, harmful, and potentially alcohol-dependent drinking” and 28% experiencing signs of depression. A 2021 study of over 2,800 attorneys in California and Washington, D.C. reached similar conclusions and also noted a significant gender disparity:

Women experience more mental health distress, greater levels of overcommitment and work-family conflict, and lower prospects of promotion than men in the legal profession and are more likely to leave as a result.

The structural challenges do not seem to be getting any better. In March 2022, Bloomberg reported that more than half of lawyer respondents to a recent survey indicated they were experiencing burnout in their jobs.

In my Head

These reports of legal practice ring true in my own experience. I spent most of my practice time working for the federal government, which has its share of challenges but at least lacks the billable hour. The brief stint I had in private practice quickly monetized time in ways that changed how I viewed the world and the people around me.

A quick personal story will illustrate this point. One Saturday morning during my time in private practice, I had started to bill some hours when my wife Caroline and I got into a fight. This particular relational miscue led to four hours of arguing. Just before lunch, we were finally through it. And that’s when I made the not insignificant blunder of forgetting that despite the trappings of the billable hour, all time is not actually money. I looked over at Caroline and asked: “Do you realize how much money this argument just cost us?”

This was not the question of a healthy human being.

I’ve heard similar stories about the challenges of the billable hour from former students of mine in private practice. It’s particularly acute in the most competitive markets, which amplifies the unhealthy practices and values that define legal practice. Some of these stem from the nature of legal work, which demands careful thinking and rigorous analysis. But I am increasingly worried about the culture of law and its fixation on perfectionism, long hours, artificial deadlines, and the lure of money. And I am worried about the kind of people it forms.

On the other hand, the most competitive markets and firms bring some of the most interesting and important cases and allow younger lawyers to hone their craft at the feet of some of law’s best practitioners. I want my students to work hard and be excellent lawyers. I’m glad to see some of them choose government service, public interest, and smaller markets, but I also hope some of them will consider larger firms with high billable hours requirements.

My hunch is that successfully navigating the pressures and pathologies of legal practice will require strong countercultural values and habits that will need to be lived out in communities of people who are willing to risk a different approach to their work. That may mean seeking fewer billable hours, reimagining the nature of legal practice, and protecting more time for family and friends. It may be easier to accomplish in firms with senior leaders who are willing to set a different tone and work toward culture change. In other cases, it may mean limiting the duration of one’s time in certain firms or markets and ensuring strong supporting communities during those years.

None of this is to suggest that legal practice should feel easy or fully accommodate personal preferences. The law is, after all, a profession, and the practice of this profession requires certain sacrifices. It may mean occasional all-nighters. It will almost certainly mean some unexpected weekends and evenings working on client matters. But even the most competitive markets leave some room for personal decisions that can limit workplace commitments. As one senior practitioner said to me, “at some point, this comes down to simple math: if you bill 2,500 hours instead of 2,100 hours, that’s 400 hours you didn’t spend on other things.”

In the World

One of the most energizing efforts in recent months has been working with some friends and collaborators to develop the Legal Vocation Fellowship, a new initiative aimed at Christian formation for early-career attorneys that launches in February 2023.

We are hoping to develop and sustain a network that is rooted in Christian practices and not, for example, in partisan politics. Toward this end, we have enlisted a range of speakers who will shed light on the ways in which Christian lawyers might see themselves:

Advocate

Peacemaker

Community Leader

Counselor

Steward

Prophet

Justice Bearer

Citizen

Child of God

By focusing on these different attributes, we hope to equip young Christian attorneys to be a more faithful presence in their workplace and to have a more holistic understanding of the role of their profession in the rest of their lives.

We are currently accepting applications for fellows from our seven regions: Atlanta, Chicago, Houston, New York City, San Francisco, St. Louis, and Washington, D.C. Our cohort model is based around monthly in person gatherings of mentors and fellows in each of our regional cohorts. We will provide content via Zoom from a range of experts:

We will supplement this time with a gathering of all of our regional fellows in St. Louis for seminars on law and theology led by me and four law faculty colleagues: Rick Garnett (Notre Dame), Ruth Okediji (Harvard), Lisa Schiltz (St. Thomas), and David Skeel (Penn).

Those of us who have been developing this initiative hope to create and sustain a community of practitioners who can fully engage with the redemptive aspects of legal practice while learning to resist and reimagine those parts that are more destructive and less humane.

Part of this effort grew out of a sense that whatever rebuilding of trust and institutions we might start to envision in this country is going to need lawyers as part of it. I hope that Christian lawyers will be active participants, even as I would like to see similar initiatives arise for lawyers in other faith traditions.

John, I have been praying for LVF, as you requested, and I am delighted to read this report on its progress.